The Concise Trustee Handbook Form is a must-have for anyone who is appointed as a trustee. This handy guide provides all the information you need to effectively administer a trust, from setting up bank accounts and records to filing tax returns. The form can be easily customized to fit your specific needs, making it a valuable tool for trustees of all experience levels. Reviewing the information in this handbook will help ensure that your trust administration goes smoothly and without any unexpected surprises.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Form Name | Concise Trustee Handbook Form |

| Form Length | 79 pages |

| Fillable? | No |

| Fillable fields | 0 |

| Avg. time to fill out | 19 min 45 sec |

| Other names | weiss handbook on trust law pdf, carlton weiss, weiss trustee handbook, weiss concise trustee handbook pdf |

WEISS’S

CONCISE TRUSTEE

HANDBOOK

__________

A GUIDE TO THE ADMINISTRATION OF AN EXPRESS TRUST UNDER THE

COMMON LAW,

FUNCTIONING UNDER THE

GENERAL

BY

CARLTON ALBERT WEISS

2d Edition | 2007

WEISS’S CONCISE TRUSTEE HANDBOOK

A Guide to the Administration of an

Express Trust under the

Common Law,

Functioning under the

General

By Carlton A. Weiss

2d Edition

2007

*Enlarged and revised

Copyright ©

All Rights Reserved.

For private educational use only. This book is published with the understanding that the author and publisher, jointly and severally, are not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional advice. All decisions made based on the material in this book are ultimately done at the discretion of the reader. Author and publisher, jointly and severally, assume no liability whatever.

Published by:

Negotiations Analysis

& Contractual Relations

Specialists (NACRS)

In care of G o l d e & P o w e r s

c/o 1930 Village Center Circle, Suite

Las Vegas, Nevada [89134]

Tel.: (702)

http://www.nacrs.org

WEISS’S CONCISE TRUSTEE HANDBOOK |

1 |

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION Page 1 |

UNDERSTANDING COMMERCE Page 21 |

TRUST BASICS Page 2 |

DOING BUSINESS Page 24 |

EXPRESS TRUSTS UNDER THE COMMON LAW Page 2 |

LIMITING LIABILITY & RISK Page 26 |

DECLARATION OF THE EXPRESS TRUST Page 4 |

BANKING Page 27 |

THE TRUST CORPUS Page 6 |

TRANSFERRING ASSETS Page 29 |

CERTIFICATES Page 8 |

ISSUING CERTIFICATES & BONDS Page 32 |

TRUSTEE BASICS Page 10 |

KEEPING MINUTES Page 34 |

POWERS & DUTIES OF THE TRUSTEE Page 11 |

PREVAILING IN LEGAL AFFAIRS Page 34 |

PRIVILEGES & LIABILITIES OF THE TRUSTEE Page 13 |

MAINTAINING PROPER I.R.S. RELATIONS Page 41 |

AUTHORIZED REPRESENTATIVES Page 16 |

CONCLUSION Page 43 |

EXPRESS TRUST vs. CORPORATION Page 17 |

SAMPLE FORMS Page 45 |

INTRODUCTION

THIS HANDBOOK is about the administration of Express Trusts created under the original American common law and functioning within the unique system of commerce in the American states, i.e., the general law merchant,1 as it stands in

The material presented herein has been reduced from various sources which the reader is encouraged to examine for his own knowledge and further understanding. The material herein has been rendered into a concise handbook format, intended to allow the reader to refer to each section for guidance on decisions regarding the most pertinent aspects of the administration of an Express Trust. So, only secondary attention has been given to all other matters.

All in all, the author’s objective by this handbook is to devise a simple guide, with clearly outlined methods and sample forms, for the effective handling of affairs of Express Trusts, while also showing the many options for growth and prosperity, and profound protections afforded by Express Trusts when created and administered properly. This book is written in a somewhat unconventional manner in order to accommodate this objective.

If the reader should find, after examining the sources, that this work has failed in its objective, then let it be attributed to a fault of the author, not to any supposed faultiness of the sources or the Express Trust itself. It will be admitted by all honest and learned2 lawyers (as it once was when a lawyer, by definition, was “learned in the law”3)

1The general law merchant is embraced under general common law, i.e., the original and unique system of commercial law in the American states, in which there is no commerce regulation of Express Trusts accept in connection with income derived from corporate stock and physical franchises under art. I, § 8, cl. 1 and 3 of the Constitution. See William A. Fletcher, THE GENERAL COMMON LAW AND SECTION 34 OF THE JUDICIARY ACT OF 1789: THE EXAMPLE OF MARINE INSURANCE, 97 Harv. L. Rev. 1513, 1514 (1984).

2 It was the strongly held belief of U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren E. Burger that

2 |

WEISS’S CONCISE TRUSTEE HANDBOOK |

that the Express Trust, especially one created with proper care to its instruments, is a far superior form of security, or organization in general, for individuals who desire to exercise their natural rights.

TRUST BASICS

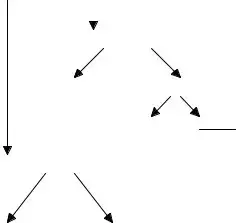

FIRST, it must be understood that any trust, regardless of the many designations applied to them, is, in its most basic sense, “a property interest held by one person (the trustee) at the request of another (the settlor) for the benefit of a third party (the beneficiary).”4 The classification applied to a trust is based primarily upon its mode of creation, in which it may be created either by act of a party or by operation of the law. In the case of the former, trusts are divided into two types: express or implied.

Creating a Trust |

|

|

Without getting |

into the various |

||

|

|

|||||

|

|

subclasses of express and implied trusts, |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

the basic difference between one created by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

express act of a party and one created by |

|

|

BY ACT OF A PARTY |

|||||

|

implied act of a party is that the former is |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

stated fully in language (oral or written), |

|

|

IMPLIED |

EXPRESS |

while the latter is inferred solely from the |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

conduct of the parties. These are very |

|

|

|

|

oral |

written |

generalized definitions so presented for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

want of space, since there are many |

|

BY ACT OF THE LAW |

|

intricacies concerning |

the true meaning of |

|||

|

the term implied. (It has been shown that, in |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

a sense, the classification of “express” trust |

|

|

|

|

|

|

can only be applied based on what is |

|

RESULTING |

CONSTRUCTIVE |

implied by the language of the instrument |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

which created the trust.)5 So, we won’t get |

|

into that. Our focus is on a particular written express trust type, and even though the above definition is essentially accurate, it does little to define the Express Trust as it is known in its fullest sense under the protections of the common law.

EXPRESS TRUSTS UNDER THE

COMMON LAW

THE MOST ADEQUATE DEFINITION of the Express Trust is to be understood from the earlier case law which has been eloquently summed up and restated into a clear, concise

3Black’s Law Dictionary, p. 695 (1st ed. 1891).

4Black’s Law Dictionary, p. 1513 (7th ed. 1999). An even more basic definition is provided therein as “[t]he right, enforceable solely in equity, to the beneficial enjoyment of property to which another person holds the legal title[.]” There are many more

5 See George P. Costigan, Jr., CLASSIFICATION OF TRUSTS, 27 Harv. L. Rev. 437,

WEISS’S CONCISE TRUSTEE HANDBOOK |

3 |

definition by Alfred D. Chandler, Esq.6 in a report submitted to the Tax Commissioners of Massachusetts on unincorporated associations.7 His study was conducted as part of a legislative investigation into their economic effect on the state in 1911; in the first part of the report, at pages

Express Trusts . . . put the legal estate entirely in one or more [persons], while others have a beneficial interest in and out of same, but are neither partners nor agents. This simple, adequate,

persons as a natural right. [Italics emphasis supplied in original; bold emphasis and bracket information added.]

What becomes clear from this definition is that the Express Trust is not merely a property interest held by one for the benefit of another like any basic trust. Rather, it is a trust created by private contract for the holding of a divisible property interest wherein the trustee is empowered by the settlor to do for a beneficiary of his (the trustee’s) choosing whatever he may do for himself as an individual sui juris.9 What has been created here is a trust organization, lawfully, by natural right. “As a general proposition, it may be asserted that one who creates a trust may mold it into whatever form he pleases, and that whatever one may lawfully do himself he may authorize another to do for him.”10 Doing so requires no benefit, privilege or franchise from any government or other

6 EXPRESS TRUSTS UNDER THE COMMON LAW: A SUPERIOR AND DISTINCT MODE OF ADMINISTRATION, DISTINGUISHED FROM PARTNERSHIPS, CONTRASTED WITH CORPORATIONS (1912).

7Mr. Chandler lucidly brought to the attention of the Massachusetts Tax Commission the misapplication of the term voluntary association to the Express Trust. It is

8 This is defined as: “Of his own right; . . . not under any legal disability, or the power of another or guardianship. Having capacity to manage one’s own affairs, not under legal disability to act for one’s self.” Black’s Law Dictionary, p. 1135 (1st ed. 1891).

9 See Pres. Woodrow Wilson’s address before the American Bar Association, at Chattanooga, Tenn. (Aug. 31, 1910), entitled THE LAWYER AND THE COMMUNITY. He says: “. . . liberty is always personal, never aggregate; always a thing inhering in individuals taken singly, never in groups or corporations or communities. The individual unit of society is the individual.” It has long been held that trustees of Express Trusts have greater latitude than ordinary trustees, simply because such trusts, created by individuals sui juris, may do whatever individuals sui juris may do. 10HARWOOD V. TRACY, 118 Mo. 631, 24 S.W. 214, 216; see also SHAW V. PAINE, 12 Mass. 293; “. . . a person who creates a trust may mould it into whatever form he pleases.” PERRY ON TRUSTS, I, §§ 67, 287 (4th Amer. ed.); UNDERHILL ON TRUSTS, p. 57 (Amer. ed.).

11See HALE V. HENKEL, 201 U.S. 43, 74 (1906).

4 |

WEISS’S CONCISE TRUSTEE HANDBOOK |

the contract.12 When done properly the trust is afforded all the

DECLARATION OF THE EXPRESS

TRUST

THE DECLARATION OF TRUST15 is the trust instrument that constitutes the trust. It has been noted in trust law that no technical expressions are required to create a valid declaration, so long as the words used make clear the settlor’s intent to create the trust or confer a benefit of some sort that would be best carried out in the form of a trust.16 A trust instrument doesn’t necessarily need to be a declaration either, for a trust may be, and often is, formed out of a simple agreement or even a will.17 But with an Express Trust, the declaration has been preferred since the beginnings of trusts under the common law of England, which otherwise shunned fictions of law. This is where careful attention to detail is most crucial, because in order to properly construe the intent of the settlor, the objects, property, and manner in which all is to be carried out must be set forth in unambiguous, precise language so as to particularly create the Express Trust; and where the intent of the settlor is unclear, under equity, interpretation is required to construe the intent of the parties, and the trust may be deemed invalid, depending on

12LAWSON ON CONTRACTS § 294, p. 381 (3d ed. 1923).

13In BERRY V. MCCOURT, 204 N.E.2d 235, 240 (1965) the court held that the Express Trust is a “contractual relationship based on trust form” and in SMITH V. MORSE, 2 Cal. 524, it was held that any law or procedure in its operation denying or obstructing contract rights impairs the contractual obligation and is, therefore, violative of Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution. Because the Express Trust is created by the exercise of the natural right to contract, which cannot be abridged, the agreement, when executed, becomes protected under federally enforceable right of contract law and not under laws passed by any of the several state legislatures. In ELIOT V. FREEMAN, 220 U.S. 178 (1911), the court made it clear that the Express Trust is not subject to legislative control. It went further to acknowledge the

14See Lee Brobst et al., U.S.A. THE REPUBLIC, IS THE HOUSE THAT NO ONE LIVES IN, available at

15This is sometimes referred to as the trust indenture for the purpose of denoting that it outlines the terms and conditions governing the conduct of the trustee as an indentured servant to the beneficiary under contractual arrangement (referred to in this sense as an indenture trustee).

16See Underhill, supra at art. 3, p. 10; see also CHICAGO M. & ST. PR. CO. V. DES MOINES UNION R. CO., 254 U.S. 196, 65 L.Ed. 219 (1920).

17UNDERHILL ON TRUSTS, art. 5, p. 19 (Lond. ed. 1878).

WEISS’S CONCISE TRUSTEE HANDBOOK |

5 |

the degree of ambiguity.18 However, when all is done properly, obviously, there can be no lawful impairment of the obligations of contract.19

Moreover, the declaration, by its terms and provisions, serves to establish the entire contractual arrangement, including the identities and positions of the parties, the trust’s name, jurisdiction and situs, and all particulars of administration, all of which the courts of equity will fully support by the principle that equity compels performance.20 The ultimate result is the creation of a bona fide legal entity21 with its own separate and distinct juridical personality;22 with standing to sue and be sued,23 and to function as a person in commerce by and through its trustee(s). The term natural person has been applied to Express Trusts by courts of equity because of its administration, being carried out by men acting as natural persons.24 Under this application, the trust’s right of

18Id. at p. 11.

19See the Constitution for the United States of America, art. I, § 10 (1789): “No State shall . . . pass any . . . Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts[.]”

20See CLEWS V. JAMIESON, 182 U.S. 461, 21 S.Ct. 845, 45 L.Ed. 1183 (1901).

21See BURNETT V. SMITH, S.W. 1007 (1922); and MUIR V. C.I.R., 182 F.2d 819 (C.A.4 1950).

22See BRIGHAM V. U.S., 38 F.Supp. 625 (D.C.Mass. 1941), appeal dismissed 122 F.2d 792 (reported in Title 26 I.R.C. 31, p. 356).

23See WATERMAN V. MACKENZIE, 138 U.S. 252 (1891).

24A generally unknown fact is that there are several types of citizens now existing in America. The trustee(s) of an Express Trust may seek protection under the Constitutions as state citizens throughout the “Union” of states, a jurisdiction outside the scope of the 14th Amendment which we will discuss in a later section. However, it should also be noted of all citizenship, 14th Amendment or otherwise, that jurisdiction over natural and artificial persons is distinguished without a fundamental difference. This stems, surprisingly, from the operation of in rem jurisdiction which underlies all Civil Law. Though all courts are familiar with the action in personam (against persons), it is the action in rem (against things) which, though practiced only in Maritime Law, stealthily operates in every civil and criminal court. This principle is one of the least understood in its entirety.

In rem jurisdiction over a man or woman can only exist if the man or woman is a slave, i.e., property or res (an object), in which case his or her disposition at law is no different than if he or he were a horse or other goods. See THE ZONG (GREGSON V. GILBERT), 99 E.R. 3:233 (K.B. 1783). In nature, in rem jurisdiction is exercised over men and women by their Creator, exclusively. Governments can therefore gain only a fictional in rem jurisdiction over men by creating various legal devices (personas) for those men to assume limited control of (e.g., citizen, taxpayer, driver, etc.). Since the device is legal fiction, a falsehood made true by force of law, this persona is

“The word ‘person’ defined. Gaius says ‘De juris divisione’ (the divisions of law) immediately preceding his division of the law; then follows, ‘De conditione hominum’ (meaning the condition or status of men).

“In the Institutes ‘De jura personarum’ precedes the expression ‘all our [civil] law relates either to persons, or to things, or to actions.’ The words persona and personae did not have the meaning in the Roman which attaches to homo, the individual, or a man in the English; it had peculiar reference to artificial beings, and the condition or status of individuals.” [Citations omitted; bold and italics emphasis added.]

In footnote 33, we get at the modern application and its implications:

“. . . The word ‘person,’ in its primitive and natural sense, signifies the mask with which actors, who played dramatic pieces in Rome and Greece, covered their heads. These pieces were played in public places, and afterwards in such vast amphitheatres that it was impossible for a man to make himself heard by all the spectators [and later by all judges]. Recourse was had to art; the head of each actor was enveloped with a mask, the figure of which represented the part he was to play, and it was so contrived that the opening for the emission of his voice made the sounds clearer and more resounding, vox peronabat, when the name persona was given to the instrument or mask which facilitated the resounding of his [legal] voice. The name persona was afterwards applied to the part

6 |

WEISS’S CONCISE TRUSTEE HANDBOOK |

contract is alienable, whereas its creators’ natural right of contract obviously is not.25 The Express Trust nevertheless possesses, inter alia, the right to all enjoyments stemming from the contracts into which it enters, as well as all the obligations imposed under such contracts. The Express Trust possesses the ability to hold/own property, engage in business transactions, and incur liabilities (including tax liabilities) as well as assume creditorship (including secured party status), like any other legal person.

THE TRUST CORPUS

THE CORPUS is the “body” of the trust, i.e., the property being held in trust for the beneficiary(s), the very

Initially, the legal minds who perfected the Express Trust in America did so to accommodate for the great obstacles in procuring special charters for corporations intended to deal in real estate, which trusts eventually came to be known as the “Massachusetts Land Trusts.” It was when those individuals came to realize the immense benefits of employing the trusts for the purpose of holding land, that they eventually expanded their utility to include the holding of personal property; these eventually came to be known as the “Massachusetts Electric Companies.” As an aside, when considering the presently hostile official attitude toward

itself which the actor had undertaken to play, because the face of the mask was adopted to the age and character of him who was considered as speaking, and sometimes it was his own portrait. It is in this last sense of personage, or of the part which an individual plays, that the word persona is employed in jurisprudence, in opposition to the word man, homo. When we speak of a person, we only consider the state of the man, the part he plays in society, abstractly, without considering the individual.” 1 Bouv. Inst., note 1. [Bold and italics emphasis, and bracket information added.]

Logic follows that if the man plays no part in a society, then he has no personal attachment or obligation thereto. The trustee(s) under a declaration of an Express Trust are only persons in the private sense because he is only a person once he has accepted the role offered to him by the settlor. Private persons may also pursue constitutional protection as natural persons, “citizens” within the meaning of Article IV, Section 2 of the Constitution, and may thereby claim entitlement to all the “privileges and immunities” of same. See generally PAUL V. VIRGINIA, 75 U.S. 168 (1868). Even though, in today’s economic situation the term “citizen” is presumed to signify the 14th Amendment citizen, the term cannot be applied to Express Trusts when administered properly. In contrast, corporations, as artificial persons, are “citizens of the United States,” within the meaning of the 14th Amendment per SANTA CLARA COUNTY V. SOUTHERN PACIFIC R. CO., 118 U.S. 394, 396 (1886).

25Man’s right of contract is considered so fundamental that even under Roman law, in its system of domestic slavery, all men, citizen or not, with the exception of slaves (the only

26The “thing” held in trust is referred to as the trust res, the

27See John H. Sears, DECLARATIONS OF TRUST AS EFFECTIVE SUBSTITUTIONS FOR INCORPORATION, § 1, p. 4 (1911). Olney

served as Attorney General in

WEISS’S CONCISE TRUSTEE HANDBOOK |

7 |

fact that the Express Trusts were initially, primarily utilized for purposes of holding and handling real estate is very significant, especially to our present situation.

The significance derives, in pertinent part, from the integral relationship between the law and the land. It is a fundamental principle of law that the land and the law go hand in hand; and, in America, without the 14th Amendment, the Law of the Land is the Constitution with its

This brings us to today. In the jurisdiction of the 14th Amendment United States public trust, precious metal, the substance of the common law, is legally merely a commodity. Back in the Republic, however, it remains the staple for payment of debts,32 though surface gold and silver are in considerably lesser quantity and without a fixed standard upon which to be traded. The Express Trust under the common law, holding real estate, silver or gold, is holding the very substance of the law under which it was

28Referred to in this sense, it is regarded in law as portable land. The basic principle of law is that the land includes everything of value extracted from it.

29See Lee Brobst et al., THE LAW, THE MONEY AND YOUR CHOICE (2003), available at

30See House Joint Resolution 192 of June 5, 1933; Pub. L.

31It should be noted that though the Express Trust is created under common law, it is not a creature of the common law as distinguished from equity, but rather, it is created under common law of contracts and not dependent upon any statutes; Equity supplements the common law. See generally

32See Constitution for the United States of America, art. I, § 10 (1789).

8 |

WEISS’S CONCISE TRUSTEE HANDBOOK |

created, thus ensuring that bond between law and land, and the powers and guarantees that come with it.33

CERTIFICATES

WHAT MAY COME as a surprise is that any trust may divide its trust property into shares and issue certificates.34 The power to issue certificates and bonds, and employ the use of an official seal35 never has been restricted to corporations.36 It is

There are several very useful and beneficial accessary [also spelled accessory] powers or attributes, very often accompanying corporate privileges, especially in moneyed corporations, which, in the existing state of our law, as modified by statutes, are more prominent in the public eye, and perhaps sometimes in the view of our courts and legislatures,39 than those which are essential to the being of a corporation. Such added powers, however valuable, are merely accessary.

They do not in themselves alone confirm a corporate character, and may be enjoyed by unincorporated individuals. Such a power is the transferability of shares. . . . Such, too, is the limited responsibility [liability]. . . . So, too, the convenience of holding real estate for the common purposes, exempt from the legal inconvenience of joint tenancy or tenancy in common. Again: There is the continuance of the joint property for the benefit and preservation of the common fund, indissoluble by death or legal disability of any partner. Every one of these attributes or powers, though commonly falling within our notions of a moneyed corporation, is quite unessential to the legality of a corporation, may be found where there is no pretense of a body corporate; nor will they

33See Bill of Rights, amend. VII (1791).

34See HART V. SEYMOURE, 147 Ill. 598, 35 N.E. 246; and VENNER V. CHICAGO CITY RY. CO., 258 Ill. 523, 101 N.E. 949.

35As a

36See

510.

37See WALD’S POLLOCK ON CONTRACTS, pp. 126, 296.

3823 Wend. 103,

39I will show you in the conclusion why this is the state of affairs today, as it was back then, and why the principles interpreted by the court in this case apply now more than ever.