In the quest for sustainable agriculture and year-round vegetable production, innovative solutions like the Walipini present promising outcomes. Originating from the Aymara Indian language meaning “place of warmth,” the Walipini, or underground greenhouse, leverages nature’s gifts to create a warm and stable environment conducive for growing vegetables throughout the year. By positioning the growing area between 6 and 8 feet underground, the design capitalizes on the earth's natural heat and the thermal constant to maintain a favorable growing temperature with minimal energy input. The combination of earth's warmth and the strategic capture of solar radiation exemplifies a harmonious interplay between traditional knowledge and modern agricultural practices. This approach not only addresses the climatic conditions of La Paz, Bolivia, for which it was originally designed but also extends its applicability to a broad spectrum of geographic and climatic zones. This introductory manual to the Walipini form covers essential aspects ranging from the reasoning behind its underground construction, the importance of proper location to maximize solar energy, design considerations for effective heat management, to the specifics of building such a greenhouse. It promises a journey into an agricultural practice that is both environmentally considerate and economically viable.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Form Name | Walipini Form |

| Form Length | 29 pages |

| Fillable? | No |

| Fillable fields | 0 |

| Avg. time to fill out | 7 min 15 sec |

| Other names | walipini how to build, byu walipini online, walipini underground online, walipini |

Walipini Construction (The Underground Greenhouse) |

Revised Version |

Benson Agriculture and Food Institute |

Brigham Young University |

Table of Contents |

|

|

Page |

Introduction |

1 |

I. How the Walipini works |

1 |

Earth’s Natural Heat |

2 |

More Free Energy |

3 |

Heat Storage |

3 |

Cutting Heat Loss – Insulation |

4 |

II. Location of the Walipini |

4 |

The Danger of Water Penetration |

4 |

Digging into the Hillside |

5 |

Maximizing the Sun’s Energy |

5 |

Alignment to the Winter Sun |

6 |

Angle of the Roof to the Sun |

6 |

Azimuth |

8 |

Obstructions |

9 |

III. Walipini Design |

9 |

Size and Cost Considerations |

9 |

Venting Systems |

10 |

Method 1 |

11 |

Method 2 |

12 |

Method 3 |

12 |

Method 4 |

13 |

Interior Drainage System |

13 |

Exterior Drainage System |

14 |

Water Collection Drainage/Heating System |

15 |

IV. Building the Walipini |

16 |

Tool List |

16 |

Materials List |

17 |

Laying Out the Building |

17 |

The Excavation |

18 |

The Walls |

20 |

Roof and Glazing |

21 |

Berms & Exterior Drainage |

23 |

Venting Systems |

24 |

Completion and Charging |

24 |

Introduction: The Walipini (underground or pit greenhouse) in this bulletin is designed specifically for the area of La Paz, Bolivia. However, the principles explained in the bulletin make it possible to build the Walipini in a wide variety of other geographic and climatic conditions. The word ‟Walipini” comes from the Aymara Indian language of this area of the world and means ‟place of warmth”. The Walipini utilizes nature’s resources to provide a warm, stable,

I. How the Walipini Works

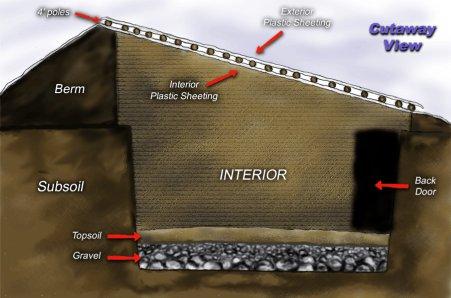

The Walipini, in simplest terms, is a rectangular hole in the ground 6 ‛ to 8’ deep covered by plastic sheeting. The longest area of the rectangle faces the winter sun

The Earth’s Natural Heat

The earth’s center is a molten core of magma which heats the entire sphere. At approximately 4’ from the surface this heating process becomes apparent as the temperature on most of the planet at 4’ deep stays between 50 and 60º F. When the temperature above ground is cold, say 10º F with a cold wind, the soil temperature at 4’ deep in the earth will be at least fifty degrees in most places. By digging the Walipini into the ground, the tremendous flywheel of stable temperature called the ‟thermal constant” is tapped. Thus, the additional heat needed from the sun’s rays as they pass through the plastic and provide interior heat is much less in the Walipini than in the above ground greenhouse. Example: An underground temperature of 50º requires heating the Walipini’s interior only 30º to reach an ambient temperature of 80º. An above ground temperature of 10º requires heating a greenhouse 70º for an ambient temperature of 80º.

More Free Energy

Energy and light from the sun enter the Walipini through the plastic covered roof and are reflected and absorbed throughout the underground structure. By using translucent material, plastic instead of glass, plant growth is improved as certain rays of the light spectrum that inhibit plant growth are filtered out. The sun’s rays provide both heat and light needed by plants. Heat is not only immediately provided as the light enters and heats the air, but heat is also stored as the mass of the entire building absorbs heat from the sun’s rays.

Heat Storage

As mass, (earth, stone, water

assisting plant growth.

Cutting Down Heat Loss

A double layer of plastic sheeting (glazing) should be used on the roof. This provides a form of insulation and slows down the escaping of heat during the nighttime. This sealed

All

When nighttime temperatures are continuously well below freezing, insulated shutters made from foam insulation board or canvas sheets filled with straw or grass can be placed over the glazing. This requires more work and storage, and in many environments is unnecessary, such as is the case in the area of La Paz, Bolivia.

II. Location of the Walipini:

The Danger of Water Penetration

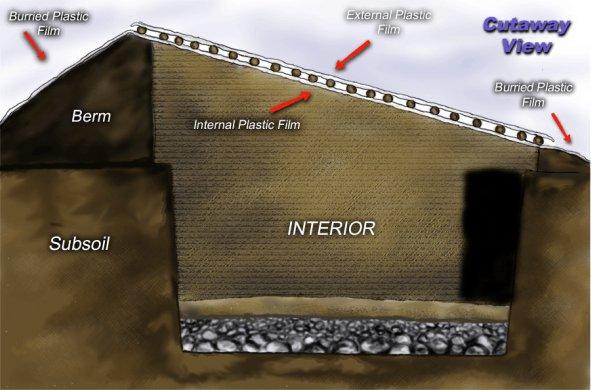

Water penetration of the walls and/or floor of the Walipini is destructive. If water seeps through the walls, they will collapse. If water comes up through the floor, it will adversely affect plant growth and promote plant disease. Dig the Walipini in an area where its bottom is at least 5’ above the water table. When all of the above ground walls are bermed, a layer of

Digging into the Hillside

Walipinis can be dug into a hillside providing the soil is stable and not under downward pressure. Since the Walipini has no footing or foundation, a wall in unstable soil or under pressure will eventually collapse.

Maximizing the Sun’s Energy

The |

sun is |

orbited by the earth once a year in an elliptical (oval) path at an average distance of 93M miles. The earth spins on its own axis creating the rising and setting of the sun. The earth is tilted at 23 1/2º from the plane of its solar orbit, which is why the sun appears lower in the sky in the winter and higher in the sky in the summer.

These variables in movement make the location of the sun, both in height and plane, different each and every day of the year. However, since the daily difference is minimal, the Walipini can be located to maximize heat in any given season. For vegetable production, this maximized location is for winter heating of its interior as this will be the most crucial time of the year for plant survival.

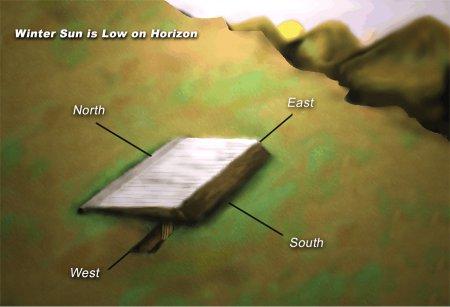

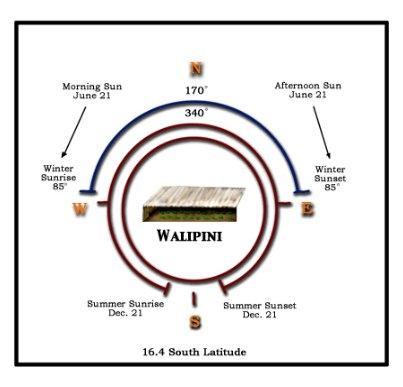

Alignment of the Walipini to the Winter Sun

Since the sun will come up in the East and go down in the West, the length of the rectangular Walipini will stretch from east to west with the tilt angle of the roof facing north towards the winter sun in the Southern Hemisphere or towards the south in the Northern Hemisphere.

This allowsthe largest

mass, the inside back (the highest) wall, to be exposed to the sun the longest as the sun moves across the horizon. Some adjustments can be made for local conditions. If winter conditions frequently produce hazy or cloudy mornings or high mountains in the east make for a late sunrise, it may be best to locate the Walipini

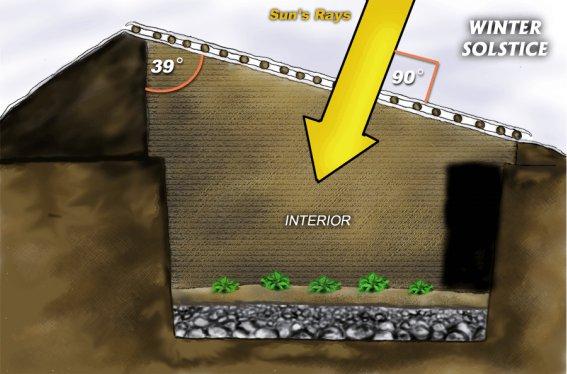

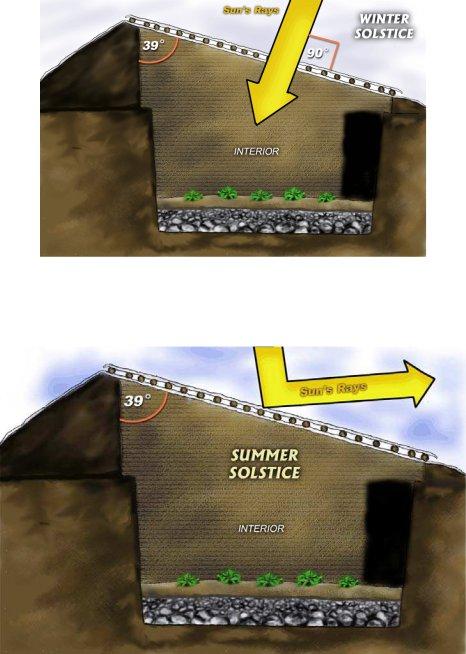

Angle of the Roof to the Sun

In order to make the simple calculation for the best angle of the roof (the plastic glazing) for maximum sun penetration at the winter solstice (the shortest day of the year), use the following rule of thumb: 1) Obtain a good map and determine the latitude on the globe. La Paz is located at 16.4º south of the equator.

2)Add approximately 23º which will make a tilt angle of 39 - 40º for the La Paz area. This will

set the glazing of the roof perpendicular to the sun on the winter solstice, which will maximize sun penetration and minimize reflection.

At the summersolstice this

angle will have the opposite effect and maximize reflection and minimize penetration.

This anglecan be

varied, but will change the basic design of maximizing heat during a winter solstice and minimizing it during the summer solstice.

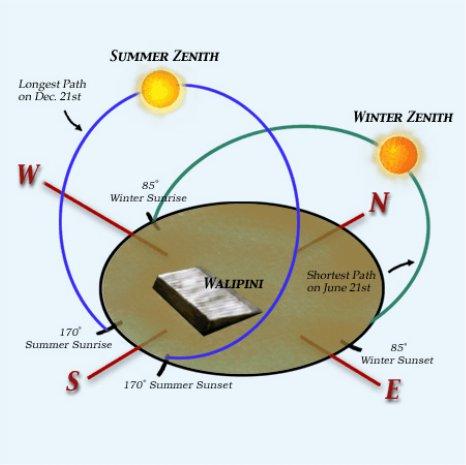

Azimuth

The change in the length of daylight from summer to winter is the result of the azimuth. The sun is higher in the sky in the summer and also goes through a much wider plan arc, or

azimuth, thus making the days longer.

At 16.4º south latitude, in (La Paz) the summer azimuth is approximately 340º while the winter azimuth angle is about 170º. This means that the winter sun rises at 85º east of north and sets at 85º west of north. Since we are seeking maximum heating in the Walipini on the winter solstice (June 21 in the Southern Hemisphere and Dec 21), the orientation of the Walipini and the angle of its glazing are designed to facilitate maximum sun penetration at the winter solstice.

Obstructions

Make sure that the Walipini is located so that its face (the roof angle facing the sun) has no obstructions such as trees, other buildings, etc. which will obstruct the sun. This is also true of the east and west sides of the structure. The only exception to this rule would be a few deciduous trees which lose their leaves in the winter. They can provide limited shading in the hot summer, but little shade in the winter.

III. Walipini Design

Size and Cost Considerations

The primary considerations in designing the Walipini are cost and

the size of the Walipini manageable and its cost as low as possible are important design considerations.

The Walipini is designed to keep costs as low as possible using the following: 1) Free labor

Venting System

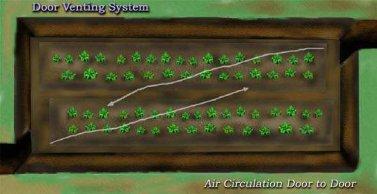

Venting can become a crucial factor in controlling overheating and too much humidity in the Walipini. Too much venting can also be a detriment and, thus, the proper balance must be

maintained for optimum plant growth. This balance is dependent upon a combination of the factors discussed in the previous three sections. Four methods of venting the Walipini will be discussed in ascending order of volume of air ventilation possible in each system. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages regarding labor, mass storage, cost, volume of air flow, etc.: 1) The first method, currently used in the La Paz model, is that of ventilating by using two doors at opposite ends of the building. It requires no additional vents, material, or labor, but it lacks the advantage of low to high convection ventilation which can move much greater volumes of air sometimes needed, if temperature and humidity climb too high.

Venting Method # 1

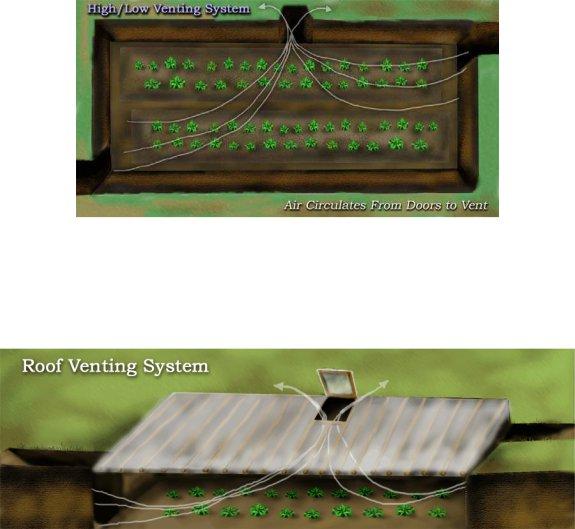

2)Method two uses the same doors with the addition of a vent of equal size as one of the doors when the vent is fully opened. This vent is centered at top of the back wall. It requires less rammed earth (labor) in the back wall (the vent area) and it provides a much greater volume of air exchange when needed. However, heat storage mass is lost in the back wall where most of the heat is collected, more interior surface area is exposed to the outside cold, a lintel must span the vent to support the roof poles and additional labor is required to contour and seal the berm at the vent on the exterior back wall.

Venting |

Method # 2 |

3)Method three uses the same doors with an additional trap door type vent of equal size in the roof.

Venting Method # 3

This vent is located in the roof at the center, back against the rear wall at the highest point.

When needed, the |

highest volume |

of air exchange, |

thus far, can be |

obtained and no |

|

is lost in the back |

wall. However, |

if the operable |

vent in the roof is |

not built |

correctly, even |

when in the |

closed position, it |

will leak rain |

water and will |

allow heated air |

to filter out when |

it is most needed. |

Only a few |

boards for the |

frame and two |

hinges are needed |

to build this 4’ x |

4’ vent. |

|

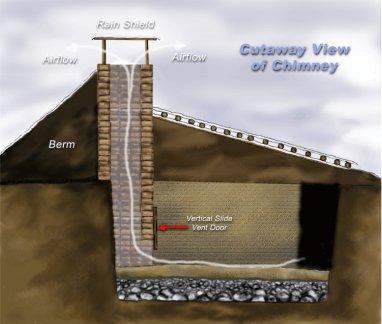

4)Method four uses the same doors in conjunction with the addition of a chimney located at the bottom center of the rear wall.

Venting Method # 4

This system provides the highest volume and best control of ventilation while retaining mass, but it requires more labor, a little more material in the adobes, 4 short vertical poles and a rain shield.

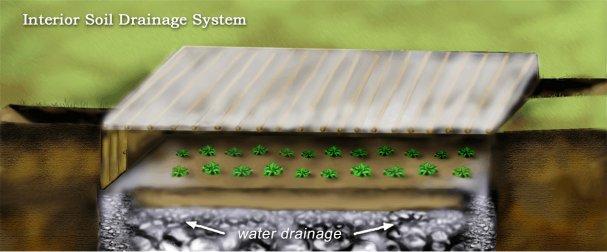

Interior Drainage System

Keeping moisture from building up to such a degree that it adversely affects plant growth and contributes to plant disease is an important aspect of the interior drainage system.

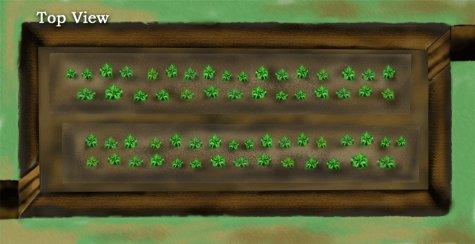

As the hole for the Walipini is dug, it is excavated to an approximate depth of 1 - 2’ deeper than it will be when in operation. This area (1 - 2’ of depth) is filled with stone, gravel and 8” of top soil. The larger stones are placed at the bottom with the gravel becoming progressively smaller as it meets the layer of top soil. The bottom of the dig will be progressively sloped from the center to the ends with a drop of 1/4” per foot. In the La Paz model this means that from the center, the bottom of the dig to each end will have an

Exterior Drainage

Water is both friend and foe of the Walipini growing system and must be handled appropriately. Exterior drainage of excess rainfall away from the Walipini is crucial.

For this |

reason berms |

must have |

sufficient |

incline away |

from the |

underground |

walls of the |

building to |

move water |

away quickly. |

A minimum |

of a quarter |

inch drop per |

running foot |

is |

recommended.

Depending upon the porosity of the soil, it may be necessary to bury a layer of clay such as

bentonite or a layer of plastic sheeting from the rammed earth wall to the perimeter drainage ditch.

How far the ditch is away from the interior wall of the building will depend upon how effectively one can seal the berms and/or move the water away from the building. Most

Water Collection Heating/Irrigation System

This system collects runoff from the roof at the front of the roof in a galvanized metal or PVC rain gutter. From the gutter water flows through a pipe into the

Each of the barrels is connected by overflow piping at the top with the overflow pipe at the last barrel exiting at ground level under the back berm to the perimeter drainage ditch.

In case of a

IV. Building the Walipini

Tool List

Hammers, shovels, picks, saws, wheelbarrows, crowbar, forms for rammed earth compaction (two 2 ‟ x 12” x 6’ planks held together by 2” x 4” or metal rods or many other type of forms can be made), 100’ and 25’ measuring tapes ( If 100’ tape is not available, measure out and mark 100’ of string or rope), levels, clear hose for corner leveling, cutting knives, hose, nozzle, hand compactors, adobe forms, drill, bits, stakes, nylon string, etc.

Materials List for a 20' x 74' Walipini

Water

20

3

3

2

1

1700 sq.’ of 200 micron agrofilm (polyethylene UV plastic) 640’ of 1” wood stripping to secure plastic sheeting to the poles Shovels, tractor or ox drawn fresno plow to dig hole

30 cubic. yds. of gravel for the floor drainage system

1 cubic yds of gravel or stone to fill the 2 drain sumps 233 cubic yds of soil will come from the excavation

22 cubic yds of top soil for planting (8” x 66’ x 12’)

94 cubic yds. for the rammed earth walls

This will leave a remainder of 109 cubic yds. for wall berms.

2700 sq’ of plastic sheeting to bury for drainage, if needed 74 ‛ of drain gutter for the lower end of roof

100’ of overthrow/drain pipe from gutter through barrel system to perimeter drainage ditch Nails

116 8” x 4” x 12” adobes for the perimeter to seal plastic roof edge

Laying out the Building

We will use the La Paz model. Select the site location as explained in section I and measure out the 12.5’ x 66’ growing area marking it by driving stakes and stretching string. Now ‟square” the area using the tape or the

mark them.

The Excavation

The hole should be dug 1’ - 2’ deeper than the growing surface. This allows room for rock/gravel fill and then the top soil. Separate the first 8” of top soil from the rest of the soil as it will be used as the top soil for growing in the Walipini. The excavation can be

As the soil is removed, remember to pile the soil in areas where it will be used for berming and the rammed walls. Moving it the least number of times will reduce labor. (Some of the rammed earth walls can be built at the same time the excavation is going on using the soil as it comes from the hole). Soil for rammed earth should contain approximately 10% moisture – just moist enough to hold its shape after being compresses in your hand.

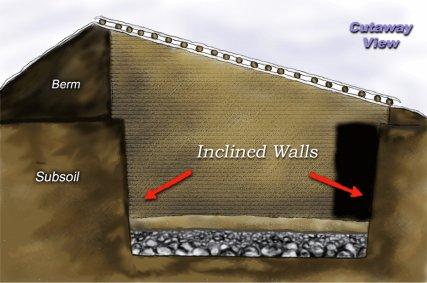

Don’t forget to dig the two channels needed for the door entrances at opposite ends of the building. It is important to note that all four vertical walls of the dig need to be sloped from the bottom to the outside at the top. A minimum of a 6” slope from bottom to top is suggested for a 6’ high wall. This will greatly reduce soil caving in or crumbling off from the walls over time.

The floor should be sloped for interior drainage from the center to each end and sump/wells dug at each end before starting to

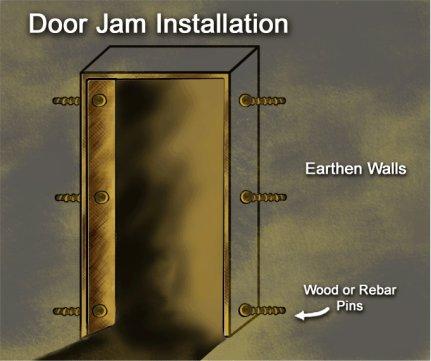

The door jams (frames) and doors should now be installed at the bottom level of the two ramps at the level of the growing surface. Door jams (frames) should be of 2” thick board stock, such as 2” x 8”s, with holes drilled at the top, middle and bottom of each side. Wooden stakes, dowels, or rebar are then driven through these six holes into the earthen wall in each jam to set the doors in plum vertical position (use a level).

Install the doors making sure they fit as airtight as possible.

Fill in any air cracks found around the door frames with adobe mud (clay, sand and straw mix). This completes the underground portion of the Walipini.

The Walls

Lay out the walls all the way around by dropping back 6” from the edge of the excavation. Using the grade stakes as the reference, make sure the soil foundation for the walls is level and uniform all the way around the building. Mark the layout of the walls with lime and begin ramming them staring at a corner using the ramming form. Mix the soil to approximately 10% moisture content before shoveling it into the form. A good rule of thumb for the 10% moisture content is

the roof, cut in to 5’ lengths laid side by side and wired and/or nailed together on top of the door frame may be sufficient. Continue moving the form and ramming the first course/level of earth until the first level is completed all the way around the building. As the form is set for the next courses as the wall goes up, always check with a level to make sure that the walls are straight up and down (perpendicular to the ground) and not leaning to one side or the other.

Begin the second course of rammed earth on top of the first at the

Be sure to wet the exposed surface of the soil at the bottom of the form each time before beginning to ram. This will increase the adhesion of the horizontal joints and strengthen the wall. Continue until the proper height has been reached on each wall. If the middle,

Roof and Glazing

Recheck and make sure that the angle of the roof is approximately 39º to 40º so it will be perpendicular to the sun’s rays on the winter solstice. Next place the twenty 4” x 16’ long poles on 4’ centers spanning the roof beginning at one end of the growing area which will place the 18th pole at the other end of the growing area. Poles 19 and 20 are placed at the ends 4’ from

poles 1 and 18 so that there is minimum 1’ overhang over the two doors on the ends of the building.

Little overhang on the front and back walls is needed, if plastic sheeting is used to protect the immediate area from erosion and water penetration. Before pinning the poles into the tops of the back and front walls, place a sheet of plastic running the full length of the interior of the building, including the overhangs, at both the top and bottom so that this interior glazing will be staked down with the end of each pole. Drill a hole in each pole and stake it into the rammed earth with rebar, a wooden stake or dowel. Fill the wall in between each pole with adobe mud the width of the wall following the angle of the poles. This will seal the area between each of the poles to prevent outside air from coming in and inside heated air venting to the outside. Now cover the entire exterior of the roof with the plastic sheeting overlapping each joint at least 6” to minimize air leakage and securing each overlap with wood stripping and nails at one of the poles. Nail stripping the full length of each pole to secure the plastic and to prevent wind damage. Place a single course of adobes all the way around the perimeter of the roof with the exception of the bottom side where the water runs off into the gutter system. This will secure the boarder of the plastic to the walls. On the lower wall the plastic must run down to the gutter system unobstructed so the water freely follows this course.

Now go inside the Walipini and finish lining the underside of the poles/roof with the plastic securing it with nailed stripping as well. Make sure to seal the overlaps to prevent heated air and moisture in the growing area from entering the dead 4” insulation air space. Now check all areas where the poles and plastic join the roof for open spaces that will leak air and fill them with adobe mud from the inside and the outside.

Next return to the outside and install the rain gutter at the lower end of the roof so that it will catch all of the run off from the glazing. Make sure that the gutter is lower at the end where the distributions of the water will take place. At the gutter exit install a

Run a pipe from the T valve inside above the door and over to the first barrel in the corner. Then run additional pipe for overflow from the first to the last barrel and then an exit pipe from the last barrel through the back wall of the Walipini over to the nearest surface drainage ditch. The roofing system is now completed.

Berming and Exterior Drainage

We now berm the exterior walls. The thicker and higher the berms the more mass and insulation

we add to the

the Walipini.

Venting Systems

The first two venting systems have already been treated. The last two venting systems require additional construction. The third simply requires the making of a frame (approximately 4’ x 4’

x4” thick in size which will allow the 4’

in the middle of the roof of the building at its highest point

way round for a better water/air seal. This trap door can be opened from below and set at different apertures according to venting needs. The forth system requires the building of a chimney with its highest point (not including the rain shield) at a minimum of 2’ above the apex of the roof of the structure. Air flow is controlled by a vertical sliding cover at the chimney opening inside of the building and by the two doors.

Completion and Charging

The basic structure of the Walipini is now finished and it is almost ready for planting. Once the Walipini is finished, it should be rechecked for air leaks and any found should be properly

sealed. Smoke generated inside the Walipini escaping to the outside will indicate where more sealing still needs to be done. Once it is confirmed that the building will seal properly, it should then be left with all doors and/or vents closed so that the mass can begin to charge with heat. Once interior temperatures are 45º and above at the coldest part of the night