In an evolving landscape where audience engagement holds the key to marketing success, the Integrated Brand Promotion (IBP) strategy emerges as a beacon for brands aiming to forge deeper connections with their consumer base. At the heart of this approach lies the harmonization of advertising efforts across various platforms, aiming not just to capture attention, but to weave a cohesive narrative that resonates with the target audience's experiences and expectations. The sixth edition of "Advertising and Integrated Brand Promotion" by Thomas C. O’Guinn, Chris T. Allen, and Richard J. Semenik delves deep into this concept, encapsulating years of academic and professional expertise into a comprehensive guide that sheds light on the nuances of modern marketing strategies. From the foundational principles of positioning and value proposition to the intricate dynamics of market segmentation and target identification, this edition serves as an essential resource for marketers seeking to navigate the complexities of contemporary brand promotion. It underscores the criticality of understanding consumer behavior and leveraging creative storytelling, thereby equipping brands with the tools needed to traverse the competitive landscape. Furthermore, the text goes beyond theoretical discussions, offering practical insights into point-of-entry marketing and the significance of making a memorable impact on new users, exemplified by strategic campaigns from industry giants like Folgers.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Form Name | Integrated Brand Promotion |

| Form Length | 30 pages |

| Fillable? | No |

| Fillable fields | 0 |

| Avg. time to fill out | 7 min 30 sec |

| Other names | advertising and integrated brand promotion pdf No Download Needed, eBook, advertising and integrated brand promotion 7th edition pdf, advertising and integrated brand promotion pdf |

Advertising

and Integrated

Brand Promotion

Sixth Edition

Thomas C. O

Professor of Marketing

Executive Director, Center for Brand and

Product Management

University of

Chris T. Allen

Arthur Beerman Professor of Marketing

University of Cincinnati

Richard J. Semenik

Professor of Marketing

Montana State University

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Advertising and Brand Promotion,

Sixth Edition

Thomas C. O’Guinn, Chris T. Allen,

Richard J. Semenik

Executive Vice President, Academic Solutions—

Business, Computers & Social Sciences:

Jonathan Hulbert

Vice President of Editorial, Business:

Jack W. Calhoun

Executive Editor: Mike Roche

Developmental Editor: Julie Klooster

Editorial Assistant: Kayti Purkiss

Marketing Manager: Gretchen Swann

Marketing Coordinator: Leigh T. Smith

Sr. Content Project Manager: Holly Henjum

Media Editor: John Rich

Print Buyer: Miranda Klapper

Sr. Marketing Communications Manager: Jim Overly

Production Service:

Integra Software Services, Inc.

Sr. Art Director: Stacy Jenkins Shirley

Internal and Cover Designer: Joe Devine, Red Hangar Design

Cover Images: iStock Photo/Shutterstock Photo

Sr. Rights Specialist: Deanna Ettinger

Photo Researcher: Susan Van Etten Lawson

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 14 13 12 11 10

© 2012, 2009

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored, or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning, digitizing, taping, web distribution, information networks, or information storage and retrieval systems, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

For product information and technology assistance, contact us at

Cengage Learning Customer & Sales Support,

For permission to use material from this text or product,

submit all requests online at www.cengage.com/permissions

Further permissions questions can be emailed to

permissionrequest@cengage.com

ExamView® is a registered trademark of eInstruction Corp. Windows is a registered trademark of the Microsoft Corporation used herein under license. Macintosh and Power Macintosh are registered trademarks of Apple Com- puter, Inc. used herein under license.

Cengage Learning WebTutor™ is a trademark of Cengage Learning.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011920095

S5191 Natorp Boulevard

Mason, OH

USA

Cengage Learning products are represented in Canada by Nelson Education, Ltd.

For your course and learning solutions, visit www.cengage.com

Purchase any of our products at your local college store or at our preferred online store www.CengageBrain.com

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Chapter 6

Market Segmentation,

Positioning, and the Value

Proposition

After reading and thinking about this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

1 Explain the process known as STP marketing.

Describe different bases that marketers use to identify target

2 segments.

3 |

Discuss the criteria used for choosing a target segment. |

|

Identify the essential elements of an effective positioning |

4 |

strategy. |

|

|

||

5 |

Review the necessary ingredients for creating a brand |

|

proposition. |

||

|

© Haywiremedia/Shutterstock

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

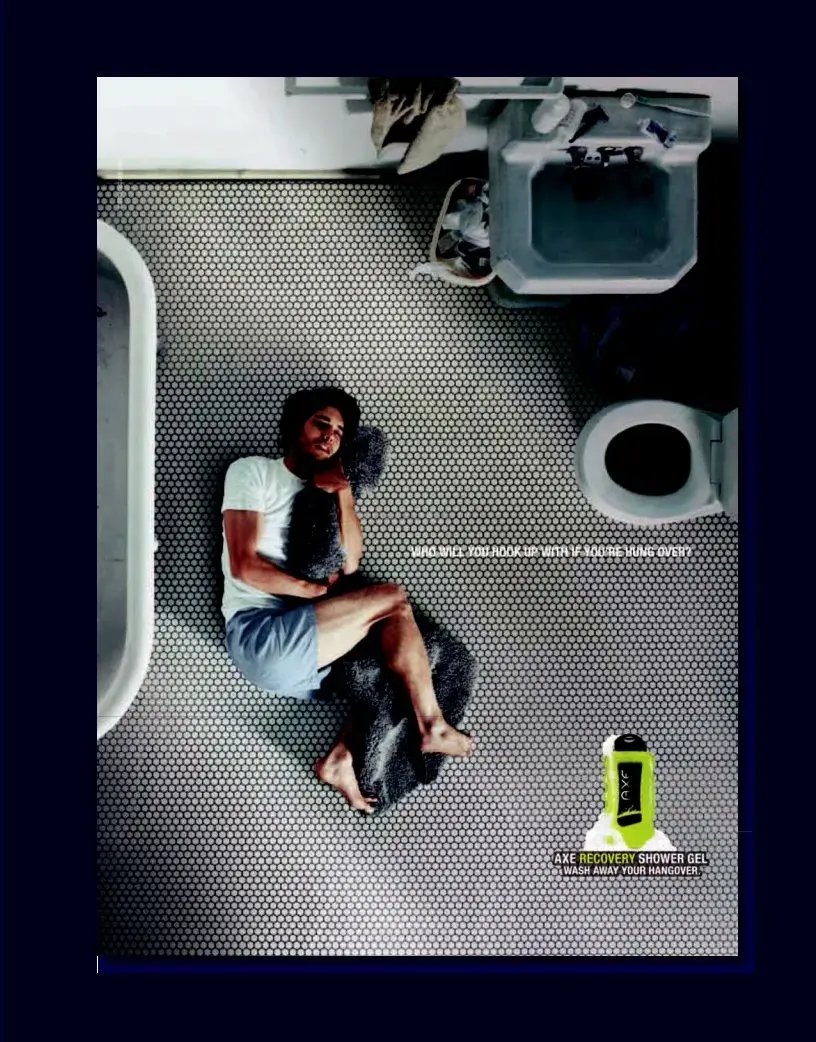

Courtesy, © Unilever USA

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

210 |

Part 2: Analyzing the Environment for Advertising and Integrated Brand Promotion |

Introductory Scenario:

How Well Do You “Tolerate Mornings”?

You know by now that advertising in its many forms is always sponsored for a reason. Generally that reason has something to do with winning new customers or reinforcing the habits of existing customers.1 However, advertising has no chance of producing a desired result if we are unclear about who we want to reach. We need a target audience.

One special problem that most companies face is reaching potential custom- ers just as they are experimenting in a product category for the first time. This is a pivotal time when one wants the consumer to have a great experience with your brand. So, for example, if we are Gillette and seek to market anything and every- thing associated with shaving, we will want one of our shavers in the hands of the consumer the first time he or she shaves.

are out of business. Developing advertising campaigns to win with

Folgers does a huge business in the coffee category but can take nothing for granted when it comes to new users. Thus, the marketers of Folgers must launch campaigns to appeal specifically to the next generation of coffee drinkers. These of course would be young people just learning the coffee habit. Attracted by coffee titans like Starbucks and Dunkin

to start brewing coffee at home, Folgers sees its big chance to get in your cupboard. To illustrate, the Folgers brand team launched an advertising initiative to attract

Working with its ad agency Saatchi & Saatchi, the Folgers brand team found another way. It started with the premise that mornings are hard, filled with emails and bosses making demands and those darn “morning people” (who for some bizarre reason seem to love sunrises). Folgers exists to help a person tolerate morn- ings, and especially to toler- ate those morning people.

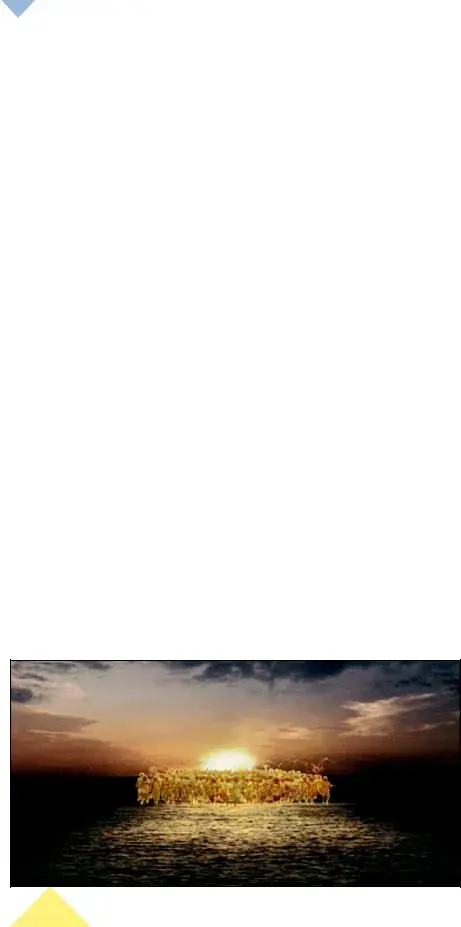

A short film, titled some- thing like “Happy Mornings: The Revenge of the Yellow People,” was produced to show Folgers as your first line of defense when the fanatical Yellow People try to invade your space first thing in the morning (that

out of the sunrise and across the lake in Exhibit 6.1).

Exhibit 6.1 The Yellow People glow like a sunrise and they want you! |

The film was also designed |

|

to steer traffic to a website |

1. Christie L. Nordhielm, Marketing Management:The Big Picture (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006).

© Procter & Gamble. Used by permission

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Chapter 6: Market Segmentation, Positioning, and the Value Proposition |

211 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

© Procter & Gamble. Used by permission

1

Exhibit 6.2 Your best defense when the Yellow People show up unannounced.

(per Exhibit 6.2) where other tools

The provocative aspect of the Yellow People film is that zero dollars were spent on media. That

(Adcritic, BestadsonTV.com, and Boards) where

“I now watch this every morning to wake up, cause it’s just so damn funny and awe- some that it wakes me right up. If I ever get rich I’m going to hire a bunch of people to dress like happy yellow people and come wake me up with that song every morning.” “I am without speech at the sheer brilliance. If commercials were like this. . . I

wouldn’t skip them on the DVR.”

“I took one look at that video and went straight into the kitchen and made a cup of coffee at 9:30 pm, because after all, I can sleep when I am dead!”

Many companies large and small share the problem we see embedded in the Folgers example. Simply stated, we must be clear on who we are trying to reach and then on what we can say that will resonate with them. Companies address this challenge through a process referred to as STP marketing. It is a critical process from our stand- point because it leads to decisions about who we need to advertise to, what value propo- sition we want to present to them, and how we plan to reach them with our message.

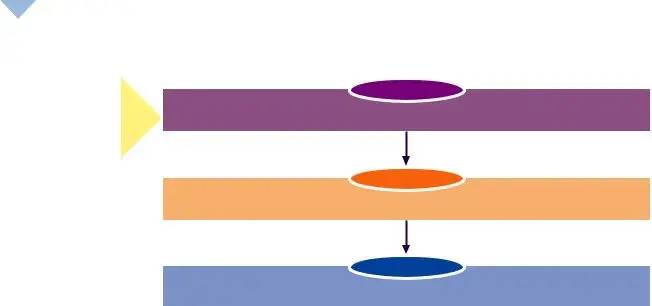

STP Marketing and the Evolution of Marketing Strategies.

The Folgers example illustrates the process that marketers use to decide who to advertise to and what to say. The Folgers brand team started with the diverse market of all possible coffee drinkers, and broke the market down by age segments. They then selected

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

212

Exhibit 6.3 Laying the foundation for effective advertising campaigns through STP marketing.

Part 2: Analyzing the Environment for Advertising and Integrated Brand Promotion

Segmenting

Breaking down diverse markets into manageable segments

Targeting

Choosing speciic segments as the focal point for marketing efforts

Positioning

Aligning the marketing mix to yield distinctive appeal for the target segment

Markets are segmented; products are positioned. To pursue the target segment, a firm organizes its marketing and advertising efforts around a coherent positioning strategy. Positioning is the process of designing and representing one

service so that it will occupy a distinct and valued place in the target consumer mind. Positioning strategy involves the selection of key themes or concepts that the organization will feature when communicating this distinctiveness to the target segment. In Folgers

it

that

Notice the specific sequence illustrated in Exhibit 6.3 that was played out in the Folgers example: The marketing strategy evolved as a result of segmenting, targeting, and positioning. This sequence of activities is often referred to as STP marketing, and it represents a sound basis for generating effective advertising.2 Although no for- mulas or models guarantee success, the STP approach is strongly recommended for markets characterized by diversity in consumers

with any significant degree of diversity, it is impossible to design one product that will appeal to everyone, or one advertising campaign that will communicate with everyone. Organizations that lose sight of this simple premise run into trouble.

Indeed, in most product categories one finds that different consumers are look- ing for different things, and the only way for a company to take advantage of the sales potential represented by different customer segments is to develop and market a different brand for each segment. No company has done this better than cosmetics juggernaut Estée Lauder.3 Lauder has more than a dozen cosmetic brands, each devel- oped for a different target segment. For example, there is the original Estée Lauder brand, for women with conservative values and upscale tastes. Then there is Clinique, a

2.For more on STP marketing, see Philip Kotler, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003), chs. 10, 11.

3.Nina Munk, “Why Women Find Lauder Mesmerizing,” Fortune, May 25, 1998,

4.Athena Schindelheim, “Bobbi Brown: How I Did It,” Inc. Magazine, November 2007,

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Chapter 6: Market Segmentation, Positioning, and the Value Proposition |

213 |

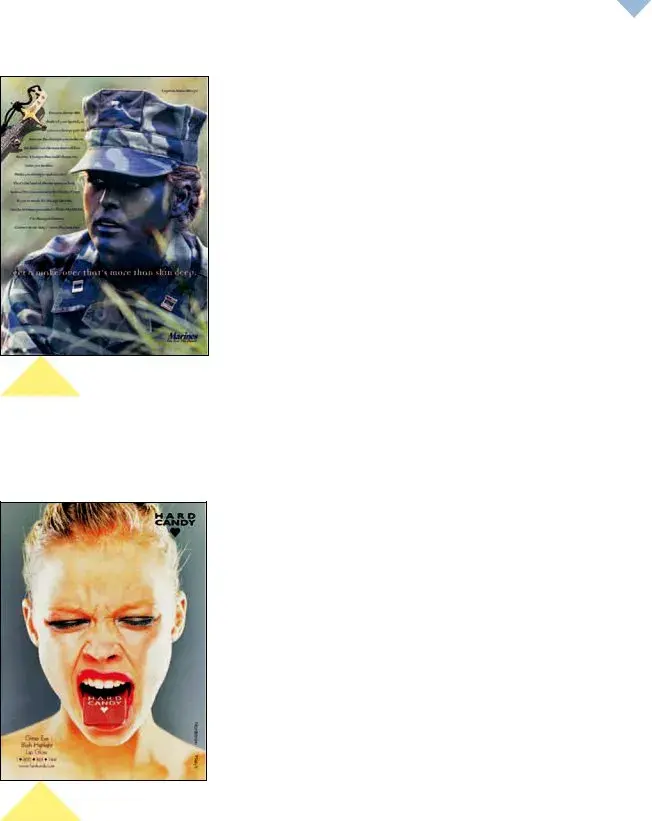

Defense has approved, endorsed, or authorized this product; Courtesy, Hard Candy

Exhibit 6.4 The U.S. Armed Forces, including the Marines, are very aggressive and sophisticated advertisers. Note how they position themselves with their advertising slogan: The Few, The Proud, The Marines (www.marines.com).

RuPaul, a

companywww.elcompanies.com.

We offer the Estée Lauder example to make two key points before moving on. First, the Folgers case may have made things seem too simple: STP marketing is a lot more complicated than just deciding to target a particular age group. Age alone is rarely specific enough to serve as a complete identifier of a target segment. Second, the cosmetics

ple shows that many factors beyond demographics can come into play when trying to identify valid target segments. For these diverse cosmetics brands, we see that considerations such as attitudes, lifestyles, and basic values all may play a role in identifying and describing customer segments.

To reinforce these points, examine the two ads in Exhibits 6.4 and

6.5.Both ran in Seventeen magazine, so it is safe to say that in each case the advertiser was trying to reach adolescent females. But as you compare these exhibits, it should be pretty obvious that the advertisers were really trying to reach out to very different segments of adolescent females. To put it bluntly, it is hard to imagine a marine captain wearing Hard Candy lip gloss. These ads were designed to appeal to different target segments, even though the people in these segments would seem the same if we considered only their age and gender.

Neither the United States Marine Corps nor any other component of the Department of

Exhibit 6.5 Hard Candy comes by its hip style perhaps in large part because of its uninhibitedly energetic founding by

Beyond STP Marketing.

If an organization uses STP marketing as its framework for strategy development, at some point it will find the right strategy, develop the right advertising, make a lot of money, and live happily ever after. Right? As you might expect, it

STP marketing yields profitable outcomes, one must presume that suc- cess will not last indefinitely. Indeed, an important feature of marketing and

To maintain the vitality and profitability of its products or services, an organization has two options. The first entails reassessment of the segmentation strategy. This may come through a more detailed exami- nation of the current target segment to develop new and better ways of meeting its needs, or it may be necessary to adopt new targets and posi- tion new brands for them, as illustrated by the Estée Lauder example.

The second option is to pursue a product differentiation strategy. Product differentiation focuses the firm

creating differences for its brands to distinguish them from competitors offerings. Advertising plays a critical role as part of the product differenti- ation strategy because often the consumer will have to be convinced that the intended difference is meaningful. For example, Schick

Gillette

of three. But does that fourth blade really deliver a better shave? How

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

214 |

Part 2: Analyzing the Environment for Advertising and Integrated Brand Promotion |

could it be better than “The Best a Man Can Get”? Following a product differen- tiation strategy, the role for Schick

blade is essential for a close shave. But next up is Gillette to shave you closer than close. And so it goes.

The message is that marketing strategies and the advertising that supports them are never really final. Successes realized through proper application of STP marketing can be

Virtually every organization must compete for the attention and business of some customer groups while

2Identifying Target Segments.

The first step in STP marketing involves breaking down large, heterogeneous mar- kets into more manageable submarkets or customer segments. This activity is known as market segmentation. It can be accomplished in many ways, but keep in mind that advertisers need to identify a segment with common characteristics that will lead the members of that segment to respond distinctively to a marketing program. For a segment to be really useful, advertisers also must be able to reach that segment with information about the product. Typically this means that advertisers must be able to identify the media the segment uses that will allow them to get a message to the segment. For example, teenage males can be reached through product placements in video games and movies; selected rap, contemporary rock, or country radio stations; and all things Internet. The favorite syndicated TV show among highly affluent households (i.e., annual household income more than $100,000) is Seinfeld, making it a popular choice for advertisers looking to reach big spenders.

In this section we will review several ways that consumer markets are commonly segmented. Markets can be segmented on the basis of usage patterns and commit- ment levels, demographic and geographic information, psychographics and lifestyles, or benefits sought. Many times, segmentation schemes evolve in such a way that multiple variables are used to identify and describe the target segment. Such an out- come is desirable because more knowledge about the target will usually translate into better marketing and advertising programs.

Usage Patterns and Commitment Levels.

One of the most common ways to segment markets is by consumers usage patterns or commitment levels.With respect to usage patterns, it is important to recognize that for most products and services, some users will purchase much more frequently than others. It is common to find that heavy users in a category account for the majority of a products sales and thus become the preferred or primary target segment. 5

For instance,

5.Don E. Schultz, “Pareto Pared,” Marketing News, November 15, 2009, 24; Steve Hughes, “Small Segments, Big Payoff,” Advertising Age, January 15, 2007, 17.

6.Deborah Ball,

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

www.wellsfargo.com, Used with permission. Ad no longer valid as an offer of product.

Chapter 6: Market Segmentation, Positioning, and the Value Proposition |

215 |

creamer every week. (Yes, thats more than 200 jars a year!) Now thats a heavy user. Conventional marketing thought holds that it is in

Although being the standard wisdom, the

heavy users may differ significantly from average or infrequent users in terms of their motivations to consume, their approach to the brand, or their image of the brand.

Another segmentation option combines prior usage patterns with commitment levels to identify four fundamental segment

Switchers or variety seekers often buy what is on sale or choose brands that offer

disappear just as quickly as it was won.

Emergent consumers offer the organization an important business opportunity. In most product categories there is a gradual but constant influx of

Emergent consumers are motivated by many different fac- tors, but they share one notable characteristic: Their brand preferences are still under development. Targeting emergents with messages that fit their age or social circumstances may produce modest effects in the short run, but it eventually may yield a brand loyalty that pays handsome rewards for the dis- cerning organization. Developing advertising campaigns to win with

7.This

8.Bonnie Tsui, “Generation Next,” Advertising Age, January 15, 2001, 14, 16.

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.