Free Living Will Forms

In a nutshell, a living will form is a special legal document that outlines an individual’s wishes regarding medical treatments that may prolong or save their life. It does not necessarily refer to health care wishes regarding other types of medical treatment, so its uses are comparatively specific.

A living will form is ideally prepared before it’s needed. This way, it can be used if the individual described in the living will can’t make medical decisions for themselves. For instance, a person might be in a medically-induced coma or otherwise unresponsive due to injuries.

In such cases, the family or medical practitioners in charge of a person in a vegetative state might wonder if that person should remain on life support, if they should be treated further, or if they should be allowed to pass away. Such questions can be answered if the individual has a living will already drafted, as it should clearly state whether the person wants to remain on life support or continue to receive life-prolonging treatment.

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare concerns have risen manifold throughout the world, and the USA is no exception. More and more people start to take an interest in creating such legal documents as a living will, healthcare advance directive, and others that can simplify difficult situations when personal health and life are under threat.

In the following article, we will touch upon health overall, caregiving, and health care options when a person cannot take action themselves. We will also discuss the options concerning end-of-life treatment that affect the quality of life and provide better social security. Plus, we will clarify the major features and ambiguities of the healthcare advance directive and determine what a healthcare proxy, a lawyer, a witness, and a notary should do to ensure the proper effect of the document.

Living wills are usually utilized by the elderly who needs caregiving or those dealing with chronic and potentially health and life-threatening medical conditions. This being said, anyone over the age of 18 can, and arguably should, draft a living will, whatever health condition, even if terminal, they currently have. Involving a trusted third party in the family decision-making will protect you and your family from having to make difficult medical (end-of-life and caregiving) decisions and take action on your own behalf if something terrible such as a severe medical condition (vegetative state) or death occurs.

Living wills can be found in the offices of family and individual health care professionals and lawyers. Services related to living will forms are also provided by online sources; the document can be obtained as a PDF or downloadable document template. If you would like to see some examples, our site provides free living will PDF templates. The PDF sample choice is ideal for use right now. You can also use our step-by-step form builder available online, which will allow you to create customizable and printable PDF living wills ideal for any situation.

Regardless of the template, a living will can generally address three main topics, which you can read about below.

Living Will – Life Support

A living will (or advance health directive) can detail the affected person’s opinion and preferences on their personal life support. In terms of a medical context, life support is any machinery or medical practice used to keep a person alive if they are in a vegetative state or are otherwise unresponsive. Furthermore, life support is used when it’s unclear whether a person will ever come out of a vegetative state.

Life support represents ongoing medical costs and potential heavy burdens for existing family members since the person receiving health care treatment obviously cannot pay for things themselves, although they are able to state their wishes in the document beforehand. As a result, a living will should outline whether the affected individual:

- Wants life support continued at any cost despite medical states

- Wants life support continued only up to a certain cost or up to a certain amount of time

- Wants life support turned off if it becomes unclear whether they will ever awaken. They may do this to spare money for their families and loved ones

Living Will – Life-Sustaining Treatment

A living will may also provide answers regarding life-sustaining health care treatment services. Such treatments are distinct from life-support – these are treatments that may be expensive, experimental, or potentially harmful to the quality of life in the event that the affected individual does recover.

An example is life-sustaining treatment services that involve removing one’s limbs or other significant bodily tissues and parts to save one’s life. A living will can tell whether the affected individual wants their tissue removed or if they would rather pass away intact.

On the other hand, life-sustaining treatment services might be too expensive for any family to reasonably accommodate. The affected individual might want to prevent their family from going into debt just to extend their life after an accident.

The answers to these questions are not always clear. For instance, an older adult who is already sickly may decide to simply pass away without the invasive medical care procedures that might extend their life for several more weeks or months. Ultimately, a living will is supposed to dispel any confusion related to these matters and make the medical wishes of the affected individual evident to be carried out by doctors.

Living Will – End-of-Life Wishes

A living will can also outline any “end of life” health care wishes. These are any wishes or requests that an affected person might have regarding the treatment of their body, the medicine that is used for their treatment, or any other matters. In many cases, such wishes have a religious or spiritual foundation or context and can help medical practitioners avoid any accidentally insensitive behaviors.

A living will can also address end-of-life wishes regarding organ donation. For instance, someone may wish for their organs to be harvested immediately so that they can be better used for other individuals. Others may opt out of organ donation to preserve their body for burial or other memorial purposes.

Where to Keep Your Living Will

You should keep your living will in a few good locations. If you spend a lot of time on the document and don’t tell anyone where to find it, even your trusted health care agent can’t point to the document if a medical professional asks them a pointed question about your care. Your doctor’s office should receive a copy at a minimum, but you should also give a copy to your medical power of attorney for a health care agent or a healthcare proxy. Keep a third copy at home in a safe location for future reference or for later editing considerations, and perhaps a fourth at a law firm involved in the drafting process.

Disambiguations

A living will is a specific document only used for a few particular cases, but it’s often confused with similar forms. Let’s break down the differences now.

Living Will and Living Trust

A living trust is a separate legal entity that an individual creates to hold or own their assets after a legal transfer. A living trust is similar to other types of trusts in that properties or assets are invested and spent for the benefit of one or more beneficiaries. However, the beneficiary for most living trusts is most often the trust creator.

Like all trusts, living trusts are also managed by trustees. The trust maker usually serves in this capacity, although some different rules can apply (especially in the case of irrevocable trusts). Trust makers can name successor trustees, too, who serve as someone to manage the trust if the trust maker becomes mentally incapacitated or is otherwise unable to make healthcare decisions and consider a caregiving action plan themselves.

A living trust, in short, is a regular trust that can help you manage your affairs so long as you are currently alive and well. Furthermore, a living trust can maintain the economic status quo for your assets and other affairs when your health condition is undermined: you are sick, injured, or otherwise potentially at your deathbed.

Upon death, a successor trustee can disperse a living trust’s assets to any named beneficiaries. Alternatively, the details of a living trust may specify that the trust remains running and active for future beneficiaries or other purposes.

The biggest similarity between both of these legal forms is that they both protect against mental incapacitation. Living wills handle deathbed of life health care decisions on your behalf when you can’t make them for yourself. Living trusts handle the management of your assets and other economic affairs when you are similarly incapacitated.

Living Will and Advance Directive

Advance directives are crucially important documents, as well. An advance directive (also known as an advance health care directive) is a legal order that encompasses any personal decisions you want to state that might revolve around your future medical care and related medical procedures when you are in a terminal condition or close to death. Like a living will, an advance directive may come into play whenever there is a severe medical situation or when you are incapacitated or cannot make life care decisions for your own needs or health. Comas, stroke, dementia, and other related health conditions able to cause death all qualify to be regulated by the advance directive.

Provided it is built properly, an advance directive can specify your preferences regarding medical treatments you wish to receive while being in a terminal condition, life-sustaining efforts, and even types of resuscitation. Furthermore, specific directions, like those involving whether medical doctors should use feeding tubes or carry out certain surgeries, may also be included in action plans of advance directives.

An advance directive can name a health care proxy, individuals like family members or partners who may be given the authority to make medical decisions and take quick action for you if you are incapacitated. A health care advance directive also does not need to be a written or formal document. Advanced directives can be in the form of verbal instructions given to a health care provider.

Technically speaking, a living will is a type of healthcare advance directive rather than the other way around. However, it’s critical to understand that an advance directive can also encompass other activities and rules (like appointing a health care proxy). In other words, not every advance directive is a living will, but all living wills are types of health care advance directives.

Living Will and DNR

A DNR form is a “do not resuscitate” order, and that’s it. A DNR does not specify whether doctors should insert feeding tubes or perform any other life extension techniques.

It only refers to resuscitation efforts. In other words, a DNR refers to situations when you (or the patient the DNR pertains to) are clinically dead. Note that this does not refer to brain death, at which point resuscitation is impossible anyway.

The order prevents EMTs or other medical professionals from attempting the revival procedures. This means they can’t perform practices like using defibrillator paddles, chest compressions, or any other techniques in an attempt to revive the “dead” patient in question.

However, doctors may still use life extension medical practices and techniques like feeding tubes, medicines, surgeries, and so on because the patient is not yet dead, and they cannot leave them without care. Furthermore, DNR orders do not require doctors to take the affected patient off of life support machinery. In terms of such requirements, a DNR is a very limited order for a specific type of circumstance.

Individuals may request DNR orders because of medical reasons, quality-of-life concerns, or religious practices. Thankfully, DNRs can easily be obtained from a physician’s office. Such legal forms are to be signed by both the patient and their primary physician (and sometimes a notary public). The original copy of the personal document has to be presented to EMTs or other doctors to prevent them from attempting resuscitation and end life.

This does mean that an EMT or other doctor won’t attempt action to revive someone with a DNR if the parties are unaware of the existing order.

Technically, a living will may contain a DNR within its writing. However, this is not among the necessary requirements.

Living Will and Medical Power of Attorney

A medical power of attorney is similar to the health care proxy mentioned before with advance health care directives. A living will (or advance directive) allows you to appoint a medical power of attorney ahead of time to act as your healthcare decision-maker in the event that you are incapacitated.

The medical power of attorney is distinct from a living will in many cases, as a living will outlines your healthcare decisions about various medical conditions (the list of such conditions is discussed previously) or actions ahead of time. A living will could theoretically make it so that you don’t need a health care proxy or medical power of attorney to make any end-of-life decisions and take action at all. This is of extreme importance when it comes to the health condition of the document’s creator. Mental health condition is as crucial for the matter.

However, if you want to leave the final decision up to the circumstances at the time, you can appoint a medical power of attorney in your living will or as a separate document.

A medical power of attorney may be useful if your initial and primary concerns are the costs for resuscitation or other life-extension medical care. If costs appear bearable, someone with medical power of attorney could tell doctors to save your life, or they could decide otherwise if things swing the other way, and you will not continue to “live.”

Medical powers of attorney or healthcare proxy responsibilities may be handled by anyone you like, but those who do it are most often family, close friends, partners, or other parties.

Living Will and Healthcare Proxy

As mentioned, a healthcare proxy is the same thing as a medical power of attorney. A healthcare proxy can be appointed in a living will or separately depending on the healthcare wishes of the individual creating the document.

Living Will Signing Requirements by State

| STATES | Signing requirements | STATE LAW |

| Alabama | Two or more Witnesses | Alabama Code, Section 22-8A-4 |

| Alaska | Two Witnesses or Notary Public | Alaska Statutes, Section 13.52.010 |

| Arizona | One Witness or Notary Public | Arizona Revised Statutes, Section 36-3282 |

| Arkansas | Two Witnesses | Arkansas Annotated Code, Section 20-17-202 |

| California | Two Witnesses or Notary Public | California Probate Code, Section 4673 |

| Colorado | Two Witnesses | Colorado Revised Statutes, Section 15-18-102 |

| Connecticut | Two Witnesses | Connecticut Revised Statutes, Chapter 368w, Section 19a-575 |

| Delaware | Two or more Witnesses | Delaware Code, Title 16, Section 2503 |

| Florida | Two Witnesses | Florida Statutes, Section 765.202 |

| Georgia | Two Witnesses | Georgia Code, Section 31-32-5 |

| Hawaii | Two Witnesses or Notary Public | Hawaii Revised Statutes, Section 327E-3 |

| Idaho | One Witness | Idaho Statutes, Section 39-4510 |

| Illinois | Two Witnesses | Illinois Compiled Statutes, Chapter 755, Section 35/3 |

| Indiana | Two Witnesses | Indiana Code, Section 16-36-4-8 |

| Iowa | Two Witnesses | Iowa Code, Section 144A.3 |

| Kansas | Two or more Witnesses | Kansas Statute, Section 65-28,103 |

| Kentucky | Two Witnesses or Notary Public | Kentucky Revised Statutes, Section 311.625 |

| Louisiana | Two Witnesses | Louisiana Revised Statutes, Section 40:1151.4 |

| Maine | Two Witnesses | Maine Probate Code, Title 18-C, Section 5-803 |

| Maryland | Two Witnesses | Maryland Annotated Code, Section 5–602 |

| Massachusetts | No Statute | – |

| Michigan | No Statute | – |

| Minnesota | Two Witnesses or Notary Public | Minnesota Statutes, Section 145B.03 |

| Mississippi | Two Witnesses or Notary Public | Mississippi Annotated Code, Section 41-41-205 |

| Missouri | Two Witnesses | Missouri Revised Statutes, Section 459.015 |

| Montana | Two Witnesses | Montana Annotated Code, Section 50-9-103 |

| Nebraska | Two Witnesses or Notary Public | Nebraska Revised Statutes, Section 20-404 |

| Nevada | Two Witnesses | Nevada Revised Statutes, Section 449.600 |

| New Hampshire | Two Witnesses | New Hampshire Revised Statutes, Section 137-J:14 |

| New Jersey | Two Witnesses or Notary Public | New Jersey Statutes, Section 26:2H-56 |

| New Mexico | Two Witnesses | New Mexico Annotated Statutes, Section 24-7A-1 |

| New York | No Statute | – |

| North Carolina | Two Witnesses and Notary Public | North Carolina General Statutes, Section 90-321 |

| North Dakota | Two Witnesses | North Dakota Century Code, Section 23-06.5-05 |

| Ohio | Two Witnesses or Notary Public | Ohio Revised Code, Section 2107.03 |

| Oklahoma | Two Witnesses | Oklahoma Statutes, Section 63-3101.4 |

| Oregon | Two Witnesses | Oregon Revised Statutes, Section 127.515 |

| Pennsylvania | Two Witnesses | Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes, Title 20, Section 5442 |

| Rhode Island | Two Witnesses | Rhode Island General Laws, Section 23-4.11-3 |

| South Carolina | Two Witnesses | South Carolina Code of Laws, Section 44-77-40 |

| South Dakota | Two Witnesses | South Dakota Codified Laws, Section 34-12D-2 |

| Tennessee | Two Witnesses | Tennessee Code Annotated, Section 32-11-104 |

| Texas | Two Witnesses | Texas Statutes, Health and Safety Code, Section 166.032 |

| Utah | One Disinterested Adult | Utah Code, Section 75-2a-107 |

| Vermont | Two Witnesses | Vermont Statutes, Title 18, Section 9703 |

| Virginia | Two Witnesses | Virginia Code, Section 54.1-2983 |

| Washington | Two Witnesses or Notary Public | Washington Revised Code, Section 70.122.030 |

| West Virginia | Two Witnesses | West Virginia Code, Section 16-30-4 |

| Wisconsin | Two Witnesses | Wisconsin Statutes and Annotations, Section 154.03 |

| Wyoming | Two or more Witnesses | Wyoming Statutes, Section 35-22-403 |

How to Create a Living Will

As far as personal health conditions and death are concerned, creating a living will document or advance directive form is not to be done lightly. You should take a lot of time to think about the preferences and what you want to be outlined in the document, especially as it pertains only to you and your medical options.

Many people find thinking of and preparing for death to be difficult at best. Take some time or even a weekend to thoroughly read about the initial steps and terms of the living will forms creation. This will allow you to consider in detail your living will health decisions and plan for action before setting out to actually create the document and prevent you from going back to modify it over and over, paying additional fees.

Steps to Make a Living Will

Step 1. Think about What to Include in Your Living Will

The first step is to think deeply about what you want your living will to comprise in connection with your state policy. This heavily depends on your current medical circumstances. Someone in perfect health condition will have a completely different living will from someone who is facing a chronic health condition that will likely be terminal at some point. However, you may have specific wishes regarding your religious practices or your desires for organ donation. Consider your mortality and the end-of-life decisions you want to be made on your deathbed carefully to avoid any mishaps. In terms of the seriousness of the document, remember that any decisions made in this document are essentially final – they cannot be taken back by any family members unless you go back and modify the document before something terrible happens.

Step 2. Choose Your End-of-life Wishes and Treatments

If you would like, read through all of the available end-of-life options and end-of-life treatments so you can write down specific answers for each one. For instance, EMTs and doctors might use multiple methods of resuscitation to preserve your life. There is a list of multiple types of health and life-support equipment that might be used to keep you alive even if you enter a coma. Furthermore, consider any wishes that you might have for your funeral, burial, or any other last rites beforehand while you are still alive.

Step 3. Select Your Healthcare Agent

For a living will to be able to have an effect in terms of health care, pick a trusted healthcare agent who is close to your family. This is often (though not always) the same person as your health care proxy or medical power of attorney. Your healthcare agent is the person directed to carry out the wishes of your living will if they are present for your medical accident or health condition. They communicate your will to physicians and witness the entire procedure, as well as the lawyer. The health care proxy agent should be someone you trust completely because they will make decisions, choose the most appropriate action regarding your health state, and ensure that your living will is carried out properly. If you would like, they may also be in charge of retrieving the document for review.

Step 4. Complete the Living Will Form

After finalizing all of your decisions, it’s time to fill out the form. Sign the living will make it an active legal document containing your signature.

Steps to Fill Out a Living Will Form

This is a sample living will to help you fill out and complete the real thing. You can use these steps to fill out our PDF living will document template or create your own using our form-builder.

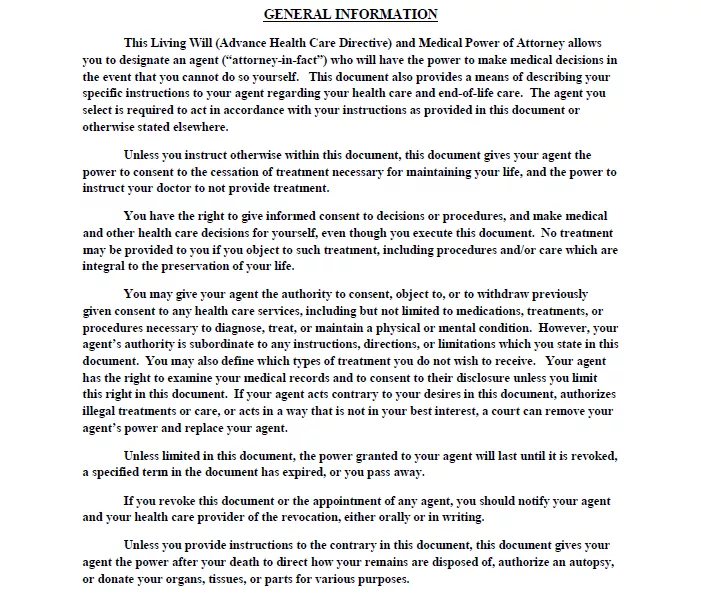

Step 1 – Review the General Information

Your living will document should have a summary of general information and an explanation of the document’s purpose. This should only last for a few paragraphs up to a page.

It also outlines your rights and what authorities you are allowed to give your agent.

Go over the text and make sure that everything is to your satisfaction, then proceed.

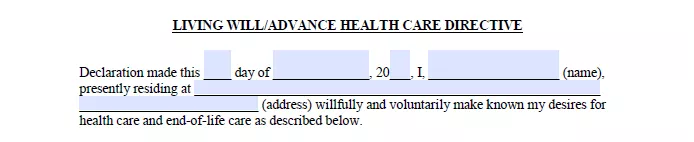

Step 2 – Living Will or Advance Health Care Directive

This is where you’ll start signing things. There will be a place where you “declare” your intentions legally by signing your:

- Name

- Age

- Date

- Primary residence

These pieces of information indicate that you are voluntarily filling out this living will (advance directive) for the purposes described in the first section.

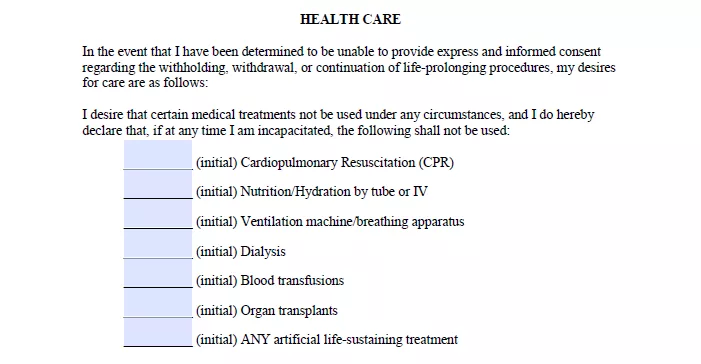

Step 3 – Health Care Decisions

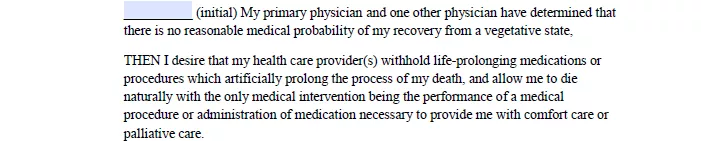

The following section deals will all your permissions, decisions, and rights concerning health care for life-prolonging or life-sustaining treatment, specifically. There will be spots for you to initial next to specific medical treatments or activities – initialing next to any of these items indicates that you do not want medical personnel to administer those treatments.

Initial next to treatments that you do not want to be carried out in the event of your incapacitation and move on.

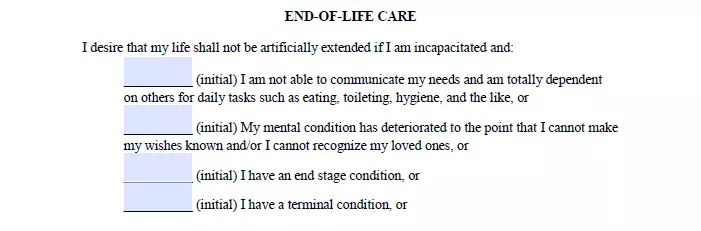

Step 4 – End of Life Decisions

The next section is about any end-of-life care medical treatment decisions. There will be a list of conditions that may be met in the event of your incapacitation. Initialing next to them indicates that you do not want medical professionals to prolong your life using the medicine, machinery, or other treatments.

Initial anywhere you like, then continue.

There should be a sentence summarizing your emotional and mental competency. In other words, make sure that the document is explicit about how you are of sound mind at the time of filling the document out.

Some living wills provide space at the bottom of the section for any additional instructions for medical treatment. Feel free to write in whatever you feel is necessary or if you have special requests for your remains.

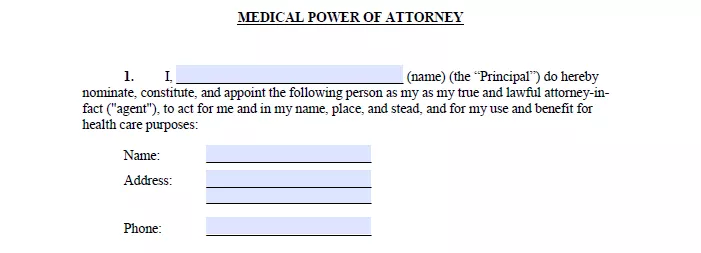

Step 5 – Medical Power of Attorney

The next section deals with medical powers of attorney. Fill out your name (which also identifies you as the “principal”), which leads to you naming and identifying a lawful attorney-in-fact or agent to act in your place for healthcare decisions if you are incapacitated.

You should next fill out the information for your medical power of attorney. Write their:

- Name

- Address

- Phone Number

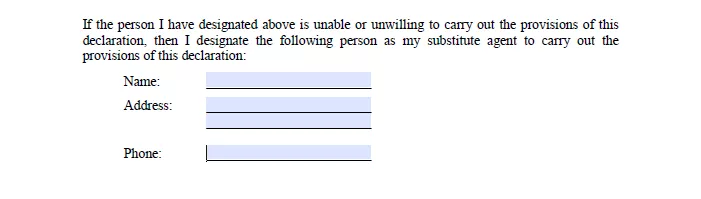

Some documents allow you to repeat this process with an additional medical power of attorney in the event that the first agent is unable to fulfill their duties. Again, fill out the name, address, and phone number of this person if applicable.

The rest of the section outlines the various duties and responsibilities that you cede to your medical power of attorney. It specifies exactly what decisions they can make so there’s no question when the time comes. Furthermore, it will include several sections in which you revoke any prior powers of attorney for healthcare and similar living will documents.

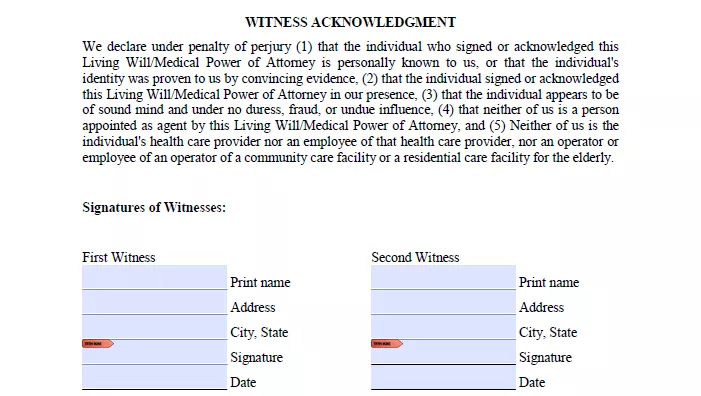

Step 6 – Witness and Notary Acknowledgements

The last section of a living will include a final signature in front of two witnesses (or the number of witnesses required by your state).

Fill out the following sections:

- Signature

- Printed Name

- Date

As to the notary requirements of advance directives, you also need to sign this document in front of a notary public.

The witness acknowledgments section beneath the document is where witnesses should fill out their identifying information. It includes their:

- Printed name

- Address

- Signature

- Date

The notary has a section of their own beneath everything else. They fill out their notary-specific information, including what state and county they are licensed to act as a notary. They’ll write in your name to indicate that they were present, then sign one last time at the bottom and include their official seal along with their commission expiration date.

For more information, read the following “Frequently Asked Questions” section.

Frequently Asked Questions

Living wills are complex documents, so let’s answer some frequently asked questions you might have about them.

Are living wills contestable?

Yes, but not because of any disagreement with the living will’s contents. Instead, a living will may be contested by a formal objection against the document’s overall validity. In other words, you must contest the will by claiming that it’s not a valid document in the first place.

You can do this in several ways. For instance, most states require that a living will include:

- A signature, a notary public’s signature, and perhaps the signature of one witness (sometimes, two witnesses)

- Signatures from adults of sound mind and body

- That the person the living will pertains to is not pregnant (or does not know they are pregnant)

- That the attending physician was notified of the will

If any of these clauses are broken, you may have cause to contest a living will. Suppose a successful case for contesting is made. In that case, doctors will usually withhold final decisions if possible but will often default to attempting to keep the affected person alive until another decision is made.

Can I change or revoke a living will?

Yes, and at any time. You must inform everyone who has a copy of the living will in writing that it has been canceled, then redraw the living will with the desired edits. You will need to go through the same witnessing and signing process as before. If your doctor’s office does not receive notification that the living will or advance directive was revoked or edited, they may decide to use the original version of the will.

How much is a living will?

A living will does not necessarily cost anything, and in fact, you can use a large number of free living wills legitimate in all states. We offer them on our site online to get started on a living will or other forms to print right now. Downloading a free living will PDF form is just the start for many people, however.

In many cases, individuals will want their living will forms (after being properly filled out and signed) notarized at a bank or another legal institution for between $10 and $15. In effect, you may also have your living will or advanced directive notarized for free if you know someone who is a licensed notary public.

On the other hand, a living will, or a health care directive might cost a lot more if you decide to have a law firm look over the document and the fees related and make sure you have everything you want to be outlined correctly. Such a precaution could help you in the event that there’s a bit of confusing writing within your living will, and you want to make sure there aren’t any problems in the event of an emergency.

In terms of the pricing, using an attorney or law firm in this way may cost you several hundred dollars in legal fees. However, the result heavily depends on the attorney in question and your existing relationship with them.

What problems can I face without a living will?

In the COVID-19 times, it is better to be prepared well enough to promote your healthcare and know what to do in case of a severe health condition. Such readiness increases the quality of life and allows to ease the work of physicians (your lawyer and attorney, as well) should your physical or mental health be no more sufficient for making serious decisions. The planning ability provided by living wills or advance health care directives is crucial. At the same time, this can be emotionally taxing to witness. Furthermore, it can be financially precarious because medical practitioners will often care to attempt to save the lives of individuals under their care without regard for ongoing medical costs. Without living wills or advance health care directives, your family members may need to make difficult decisions regarding how your life is sustained under certain conditions or how you are resuscitated without knowing your opinion and preferences on things concerning your own health condition.

A living will takes care of all of these uncertainties and makes things easier for you, your family members, and your family doctor in the event that you are incapacitated.

We hope the information from this article will be of assistance should you consider minimizing negative experiences for your family and, perhaps, yourself in a situation of great urgency and pressure. Ensure you consult your lawyer before creating documents of such kind. Most importantly, check the information concerning the power of attorney, your future health care proxy, witnesses, and a notary to ensure legitimacy and desired effect.