Free Durable Power of Attorney Forms

While most people have heard of the durable power of attorney, these critical forms are still not well understood by the public. A person with power of attorney form does not have to be an attorney or even a member of your family. They just need to be a person who understands and respects your values, will work for your well-being, and who you trust to make decisions on your behalf.

There are several types of this legal document, but we’re looking specifically at durable power of attorney (DPOA) forms. These forms give the person you choose, your attorney-in-fact, the right to make certain decisions for you even when you become incapacitated.

The truth is that almost all adults should have someone designated as their DPOA since it’s unpredictable when or how you might be incapacitated.

Build Your Document

Answer a few simple questions to make your document in minutes

Save and Print

Save progress and finish on any device, download and print anytime

Sign and Use

Your valid, lawyer-approved document is ready

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

What is a Durable Power of Attorney? (DPOA)

Durable power of attorney forms are used to give someone the right to make important choices for you and your estate in the case that you are incapacitated and cannot make those choices for yourself.

There are two general circumstances where POA forms are the most common: financial and medical.

Most people are more familiar with the medical power of attorney. This is when you designate someone to make important medical decisions on your behalf should you be unable to make them for yourself. Those choices can include the kind of care you receive while you are incapacitated, whether you are treated with life-saving interventions or comfort care, and more.

Someone who has financial powers of attorney, on the other hand, will make decisions about how your estate should be managed if you are incapacitated. They can make decisions about when to buy or sell property, how to invest your finances, and even sign checks and pay bills on your behalf.

Since durable power of attorney forms allows your agent to act on your behalf even when you are incapacitated, it’s important to choose someone you trust and who knows how you would like your finances managed in an emergency.

Your attorney-in-fact can also be involved in estate planning, executing estate planning documents, handing your social security payments, and other financial affairs. You can give your attorney-in-fact access to:

- Bank accounts

- Retirement accounts

- Investment portfolio

- Government benefits

- Miscellaneous

It is also possible to customize your durable power of attorney so that you have more control over what kinds of powers you give your attorney-in-fact. You can also designate different people as your attorney-in-fact for different matters.

For instance, you may want to designate one child as your medical agent but choose a different relative to have financial powers of attorney.

Or you may want to allow someone to sign checks, pay bills, and handle other routine financial matters without giving permission to make changes to your investments and handle real estate transactions.

Durable vs. General POA

There are several varieties of power of attorney, and you need to know which variety you are using and why.

For instance, you might give someone medical power of attorney with a general form. Unfortunately, since that form does not authorize them to act on your behalf after you have been incapacitated, they could not make medical decisions for you.

That’s the main difference. A general POA only grants rights while you competent and are not considered incapacitated, but a DPOA document allows the person you designate to make decisions even after you cannot.

A durable power of attorney expires when you die as well as in a few other circumstances. For instance, if your spouse is granted durable power of attorney and you later divorce, their DPOA will not be considered valid in most cases. However, you can renew the DPOA after your divorce if you would still like your ex to act as your attorney-in-fact.

Who Needs a Durable Power of Attorney?

In short, all adults (over the age of 18) should have someone designated with a DPOA. It’s important to have this form filled out as soon as possible.

While it would be nice if life were predictable and easily anticipated, that simply isn’t true. The unfortunate reality is that car accidents, strokes, and other potentially incapacitating accidents happen every day and to people of all age groups.

Once you are an adult, it’s important to make sure that you have someone designated who can help manage your medical and financial concerns. By default, if you do not have anyone designated with a durable power of attorney, your closest relatives will make choices for you.

However, your family is likely not to know what you would want if you haven’t discussed the possibility of this situation before. Many people also do not want their closest relatives making choices for them.

The only way to prevent a family member who either doesn’t know or doesn’t respect your values and wishes from making important financial and medical decisions is to give someone else DPOA.

POA can also be used to make difficult situations like Alzheimer’s disease easier to manage. A DPOA combined with advance directives gives you a lot more control over your care in case you become incapacitated.

While a DPOA is still most common in cases of elder care and preparing for end-of-life decisions, all adults should have a POA. More importantly, all adults should have discussions with the people they love and trust about what they would want should they become incapacitated.

Options for Medical Decisions

Medical decisions are some of the more complex legal matters to be decided, and it’s important that you make sure you give (and withhold) the legal powers of attorney you want to.

Your medical power of attorney can make choices about what treatment you’ll receive and which treatments are refused. They can also decide whether you will be transferred to a different hospital if doing so is recommended.

Your DPOA agent can also decide whether you should be admitted to a long-term care facility. They can decide between different care plans. Though DPOA expires when you pass, they will often also decide whether to authorize organ donation if death seems likely.

To help make this process easier, you can fill out other medical forms that outline your wishes. A DNR (do not resuscitate) order is one of the most common, but there are other forms that provide more detailed care options. Here is a brief summary of what some of these medical forms are and what they can do.

Do Not Recuscitate (DNR):

DNR orders tell healthcare providers that you would not want to be revived, even if medically possible. These forms can be customized to specify specific circumstances in which you would not want them to attempt to revive you. For instance, many people choose to fill out a DNR so that they will not be revived if brain damage or lowered mental capacity is likely.

Medical Power of Attorney:

Medical power of attorney is another common form that allows you to designate someone to make medical decisions on your behalf if and when you cannot. For instance, if you are in surgery and there are complications, or your surgeon discovers that you need a more complicated or different kind of surgery, they may contact your medical agent or attorney for that decision. If the POA is also durable, your medical power of attorney may make health care decisions for you if you are incapacitated due to illness or accident.

Living Will:

Living wills are distinct documents from a last will and testament. Instead of discussing how you would like your estate to be managed after passing, a living will details the kind of medical care you would like to receive at end of life. Key decisions can include when your care providers should switch to comfort care instead of trying to prolong your life and which kinds of care you would prefer.

For instance, many organ donors ask that doctors not perform any intervention that would make donation impossible should they pass. Another consideration for your living will is whether pain control is more important to you or whether you would prefer your care providers manage your pain while also preserving your mental clarity.

Your agent is required to follow your health care directives unless you specifically give them the power to override your previous medical decisions.

You can also customize the kinds of power your POA grants. For instance, if you live in another state or country than the rest of your family, it might be helpful to have someone who has POA until a designated family member who also has POA is present.

Steps to Getting a Durable Power of Attorney Document

1. Decide Who to Designate as Your Agent

Before you create a DPOA, you need to know who will authorize. You should also talk with the person before filling out the forms. That way, you can make sure that they are willing to act as your agent and feel up to the job.

2. Decide Between Financial, Medical, or Both

You will also need to decide what rights you’re giving and whether they can act as your financial and medical POA or only one of the two.

Part of this decision will also be choosing the specific power(s) you would like to give your agent and disclosing the information they need to make good choices on your behalf.

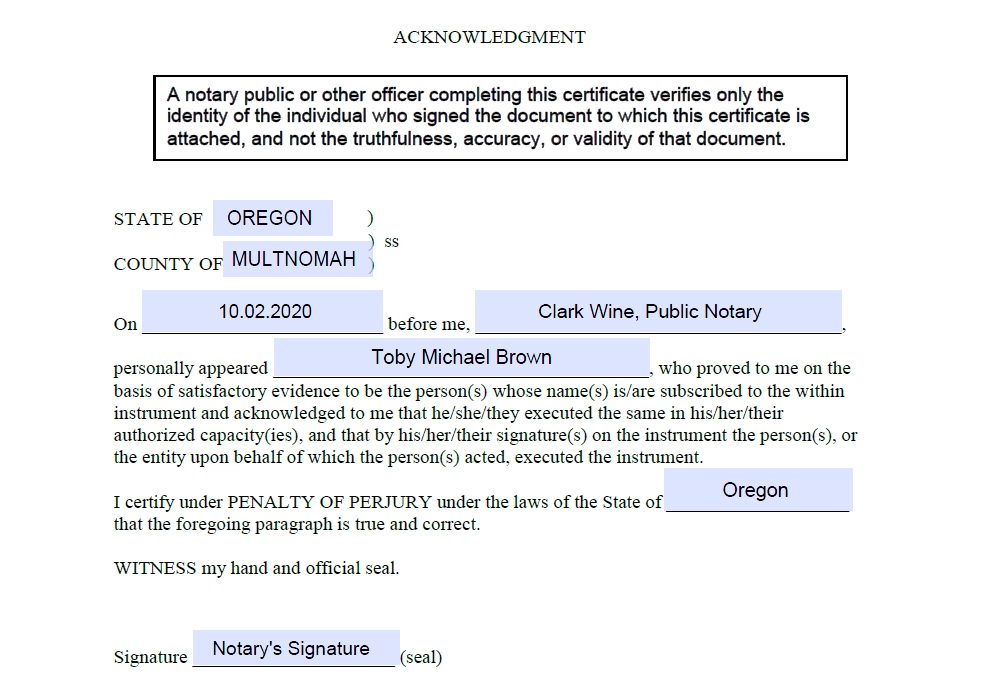

3. Get Your Durable POA Notarized and Filed Appropriately

Your DPOA will almost always need to be notarized to be considered valid. You should keep a copy, as should anyone authorized in your DPOA, as well as your lawyer.

Some states may require that your DPOA and associated documents also be filed with various state offices. You should always check and see what requirements you have to meet in your state before filing your DPOA.

Durable POA Signing Requirements by State

| STATES | Signing requirements | STATE LAW |

| Alabama | Notary Public | Alabama Code, Section 26-1A-105 |

| Alaska | Notary Public | Alaska Statutes, Section 13.26.600 |

| Arizona | Notary Public and One Witness | Arizona Revised Statutes, Section 14-5501 |

| Arkansas | Notary Public | Arkansas Annotated Code, Section 28-68-102 |

| California | Notary Public OR Two Witnesses | California Probate Code, Part 2 – Powers of Attorney Generally |

| Colorado | Notary Public | Colorado Revised Statutes, Section 15-14-705 |

| Connecticut | Notary Public and Two Witnesses | Connecticut Revised Statutes, Chapter 15c, Section 1-350d |

| Delaware | Notary Public and One Witness | Delaware Code, Title 12, Section 49A-105 |

| Florida | Notary Public and Two Witnesses | Florida Statutes, Section 709.2105 |

| Georgia | Notary Public and One Witness | Georgia Code, Section 10-6B-5 |

| Hawaii | Notary Public | Hawaii Revised Statutes, Section 551E-3 |

| Idaho | Notary Public | Idaho Statutes, Section 15-12-105 |

| Illinois | Notary Public and One Witness | Illinois Compiled Statutes, Chapter 755, Section 45/3-3 |

| Indiana | Notary Public | Indiana Code, Section 30-5-4-1 |

| Iowa | Notary Public | Iowa Code, Section 633B.105 |

| Kansas | Notary Public and Two Witnesses | Kansas Statute, Section 58-652 |

| Kentucky | Notary Public and Two Witnesses | Kentucky Revised Statutes, Section 457.050 |

| Louisiana | N/A | No Statute |

| Maine | Notary Public | Maine Probate Code, Title 18-C, Section 5-905 |

| Maryland | Notary Public and Two Witnesses | Maryland Annotated Code, Section 17–110 |

| Massachusetts | Two Witnesses | Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 190B, Section 5-103 |

| Michigan | Notary Public and Two Witnesses | Michigan Compiled Laws, Section 700.5501 |

| Minnesota | Notary Public | Minnesota Statutes, Section 523.01 |

| Mississippi | Notary Public | Mississippi Annotated Code, Section 87-3-105 |

| Missouri | Notary Public | Missouri Revised Statutes, Section 404.705 |

| Montana | Notary Public | Montana Annotated Code, Section 72-31-305 |

| Nebraska | Notary Public | Nebraska Revised Statutes, Section 30-4005 |

| Nevada | Notary Public and Two Witnesses | Nevada Revised Statutes, Section 162A.220 |

| New Hampshire | Notary Public | New Hampshire Revised Statutes, Section 564-E:105 |

| New Jersey | Notary Public and One Witness | New Jersey Statutes, Section 46:2B-8.9 |

| New Mexico | Notary Public | New Mexico Annotated Statutes, Section 45-5B-105 |

| New York | Notary Public | New York Consolidated Laws, Section 5-1501B |

| North Carolina | Notary Public | North Carolina General Statutes, Section 32C-1-105 |

| North Dakota | N/A | No Statute |

| Ohio | Notary Public | Ohio Revised Code, Section 1337.25 |

| Oklahoma | Notary Public | Oklahoma Statutes, Section 58-1072.2 |

| Oregon | N/A | No Statute |

| Pennsylvania | Notary Public and Two Witnesses | Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes, Title 20, Section 5601 |

| Rhode Island | Notary Public | Rhode Island General Laws, Section 18-16-2 |

| South Carolina | Notary Public and Two Witnesses | South Carolina Code of Laws, Section 62-8-105 |

| South Dakota | Notary Public | South Dakota Codified Laws, Section 59-12-4 |

| Tennessee | N/A | No Statute |

| Texas | Notary Public | Texas Statutes, Estates Code, Section 751.0021 |

| Utah | Notary Public | Utah Code, Section 75-9-105 |

| Vermont | Notary Public and One Witness | Vermont Statutes, Title 14, Section 3503 |

| Virginia | Notary Public | Virginia Code, Section 64.2-1603 |

| Washington | Notary Public and Two Witnesses | Washington Revised Code, Section 11.125.050 |

| West Virginia | Notary Public | West Virginia Code, Section 39B-1-105 |

| Wisconsin | Notary Public | Wisconsin Statutes and Annotations, Section 244.05 |

| Wyoming | Notary Public | Wyoming Statutes, Section 3-9-105 |

How to Fill Out a Durable Power of Attorney

Our DPOA form is designed specifically for finances, not health care, so you’ll need different attorney documents for medical considerations.

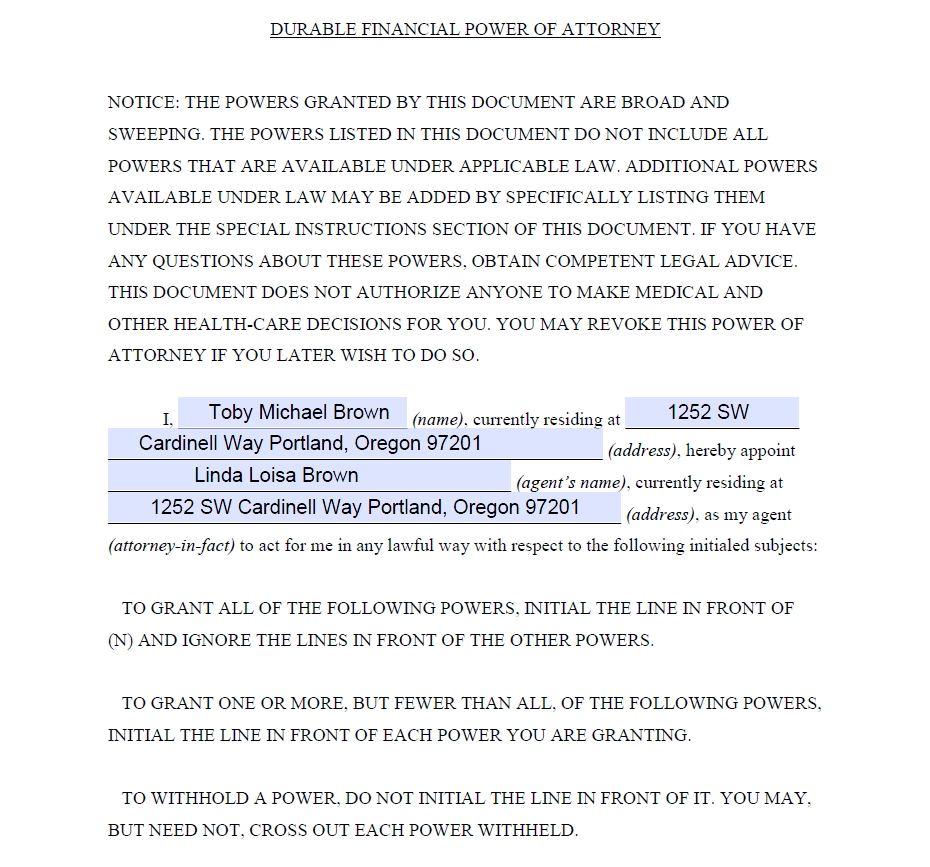

1. Fill Out Personal Information About Yourself (the Principal) and your Attorney-in-Fact

If you are filling out a form, the next step is to fill out you and your agent’s personal information.

You will always need to file using your legal name, even if you go by a different name. If you reside in multiple states, you may need to file multiple DPOA so that they are valid in each state.

Optionally, you can consult with a lawyer to create a customized DPOA form, but you’ll need similar documentation.

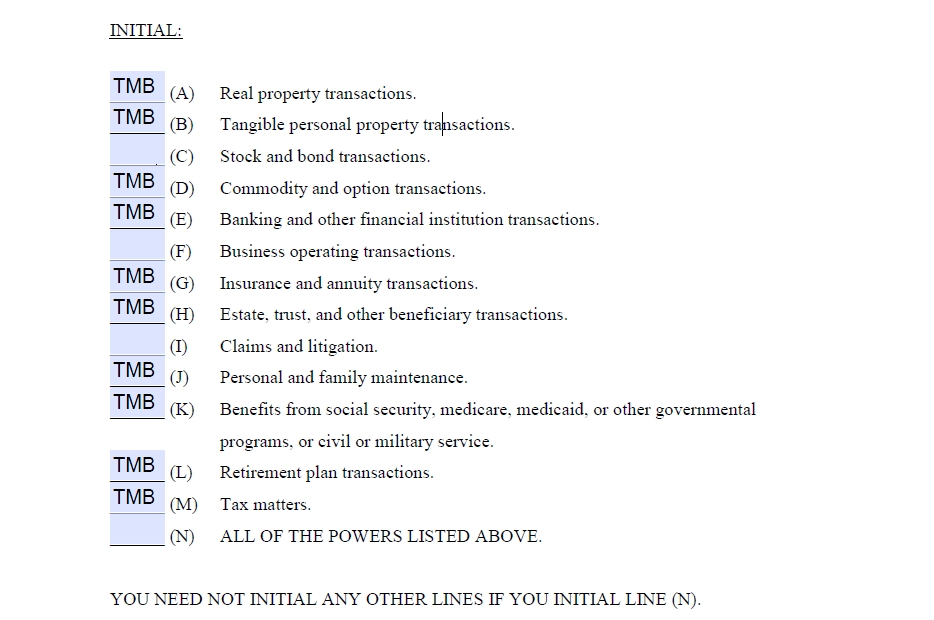

2. Specify the Granted Powers

If you are providing your agent with financial power, you will have to fill out exactly which powers you would like them to have. You’ll initial next to anything you’re granting, and leave other powers blank.

You may also need to provide financial account documentation in addition to granting financial authority. That is separate from the main DPOA form, but it’s helpful to complete it at the same time.

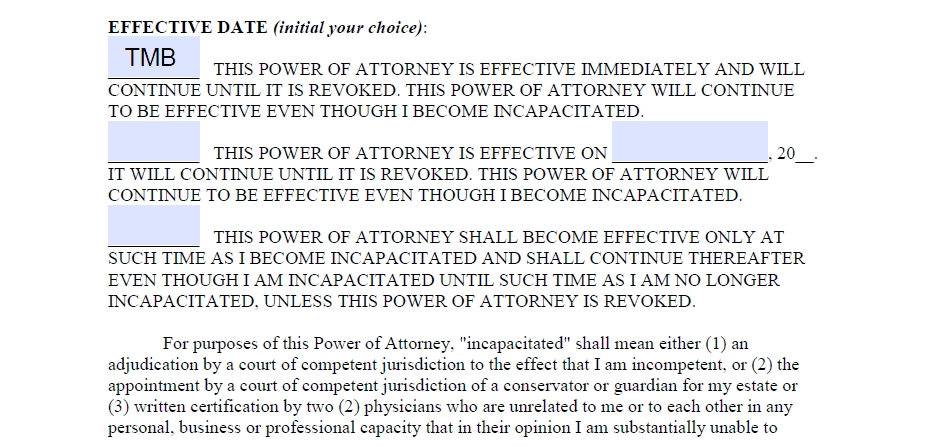

3. Indicate Effective Date

When you create a power of attorney, you will also choose an effective date. That date is the day the POA comes into effect, and the document is not considered valid before that date. This gives you a few more options and also allows you to prepare a DPOA before your marriage or other important life events. You can also make it valid only during the time you are considered incapacitated.

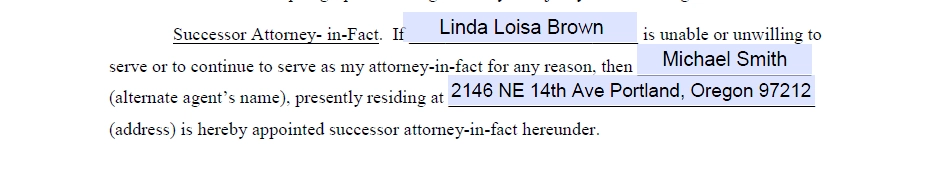

4. Choose an Alternative Agent

It is a good idea to choose a successor attorney-in-fact in case the initial agent is not able or willing to do their duties. Here, indicate the name of the first representative and the details of the alternative one.

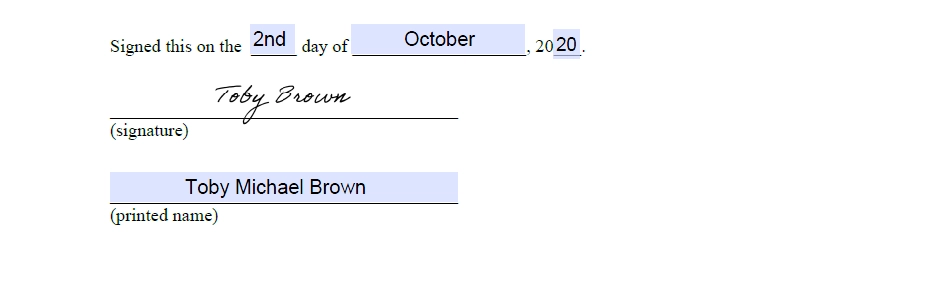

5. Review the Information and Sign the Form

We recommend going over your entire DPOA form before getting it notarized, just to make sure everything is as correct and accurate as possible.

You can always update your DPOA later, but you don’t want a clerical error to cause problems should you become incapacitated before the problem can be corrected.

Once the filled information has been reviewed and deemed correct, you can finalize the process by entering the date of completion, writing your name, and signing the document.

6. Notarize and File Your Completed Durable POA

Your DPOA may need to be notarized, depending on state law, with at least one witness. It will also need to be signed by you and your agent at the same time. Chances are that you will need several duplicates of your DPOA form to file the form appropriately.

You should also give at least one copy to your agent and your lawyer to keep as well as keeping one yourself.

Frequently Asked Questions

What should I consider when selecting an agent?

You should consider your relationship and how much you trust the person you’re considering. Are there any reasons they might decide to act against your wishes given the opportunity? Ideally, you should pick someone who knows you well and who understands and respects your wishes for the future.

What happens if the principal dies?

If the principal of a DPOA expires, the DPOA is no longer considered valid. Agent rights revert to the spouse or closest living family member if the agent is not also one of those individuals.

The principal must meet accepted medical standards of death. A coma or similar condition is not the same.

How do you relinquish durable power of attorney?

You can contact the principal and request that they revoke the power of attorney if you would like to relinquish your POA. Alternatively, you can decline to act. When you officially decline to act, someone else may be assigned to act instead, although this process can often lead to court battles. You may or may not be required to participate in a court case, depending on the circumstances and your relationship to the principal.

How much does it cost to create a DPOA?

While the exact cost of a DPOA varies from state to state, it’s not an expensive process. Online forms can typically be filled out and filed for $50 or less. If you consult with a lawyer to create a customized DPOA or receive guidance, you will also need to pay for their time.

Can an agent abuse their power?

Yes, in some circumstances an agent may be able to abuse their power. That’s why it’s important to carefully select who you give POA rights. You also need to consider what powers you are giving them and set out legal documents like Advanced Directives and a Last Will and Testament to ensure that your affairs are handled properly.

The more you decide on now, the less room there is for your agent to cause problems later.