Last Will and Testament Template

A last will and testament is a legal document specifying how you wish your property to be allocated among your chosen beneficiaries after your death. In most states, it’s mandatory for two adult witnesses to confirm the correct procedure by signing the will alongside you.

Build Your Document

Answer a few simple questions to make your document in minutes

Save and Print

Save progress and finish on any device, download and print anytime

Sign and Use

Your valid, lawyer-approved document is ready

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

What Is a Last Will and Testament?

A last will and testament is a binding legal document that determines how your property will be disbursed after your death. This can be both real property (land, buildings, etc.) and personal property (furniture, jewelry, vehicles, stocks, other savings, etc.), and in today’s digital age, it can even include online assets such as social media accounts, cryptocurrency, or online shopping accounts.

This property will typically be distributed to your children or spouse. However, you can also will your wealth to a charitable foundation or other private organization. Last, you can set aside a portion of your money to cover funeral expenses.

A video explanation:

Key Terms

Before we go any further, there are a few legal terms that you’ll need to understand:

- Testator (testatrix for women):The person leaving the last will. You can also add a clause stating that all gendered terms should be assumed to be gender-neutral. Again, this isn’t legally required, but it can be helpful in some cases, for example, if your executor is a woman and your alternative executor is a man. Writing one short clause is easier than typing “executor or executrix” 200 times.

- Beneficiary:The person who receives your money or other assets, typically called an “heir” in everyday speech. A beneficiary can also be an organization such as a charity or church.

- Executor (executrix for women): Sometimes called a “personal representative,” your executor ensures that the instructions in the last will are carried out. They are responsible for settling your affairs according to your instructions. For ethical reasons, the executor cannot be a beneficiary of the will. Also, an executor of the will can be entitled to reasonable compensation for their time and effort in administering the estate.

- Assets: Real estate/houses, personal property, cash, bank account balances, and other forms of wealth or possessions.

- Estate: The sum total of all of your assets and debts.

- Witness: The person who signs your will and who can be called on to verify its validity if necessary.

- Guardian: The person who will take guardianship of your children or other dependents after your death. A guardian can also be provided for pets.

- Probate: Legal process that takes place after one’s death. The probate court determines whether your last will is valid and authorizes the executor to carry out your instructions.

The 6 Steps to Creating a Last Will

1. Choose the Type of Will

The first step in creating your last will involves deciding on the type of will that best suits your needs:

Option 1: Self-Created Will

While you can choose to write your own last will and testament, called a holographic will, this approach carries risks. These handwritten wills are not universally accepted across all states, can inadvertently introduce conflicting stipulations, may be difficult to locate when required, and are more susceptible to legal challenges.

To circumvent these issues, consider using a fillable last will and testament template that incorporates key clauses in appropriate legal language. Alternatively, our step-by-step builder can guide you comprehensively, ensuring compliance with your state law and thereby reducing the chance of invalidation.

IMPORTANT: Although most states acknowledge holographic wills, they are handwritten and unwitnessed, making them less preferable due to potential legal complexities.

Option 2: Seek Legal Assistance

Engaging the services of an attorney is another approach for crafting your last will. Legal professionals ensure your document fulfills all state-specific requirements, but the associated costs can be substantial, varying by attorney and the complexity of your last will and testament.

Note: It’s advisable to consult with an attorney, despite costs, when bequeathing assets to recent acquaintances or disinheriting a family member.

2. Catalog Your Assets

Before finalizing your will, you need to itemize your assets eligible for disposition. Certain personal property, like jointly owned real estate or digital assets, may have specific legal stipulations. Similarly, any assets earmarked in a trust, insurance policy, retirement plan, or stocks cannot be bequeathed again.

Bear in mind that assets already assigned in a trust, retirement plan, or stocks are not eligible for further bequeathment in your will. Similarly, life insurance proceeds are typically directed to your named beneficiaries and are not governed by your will.

To simplify, consider adding a residuary estate clause. After accounting for major assets, this clause designates a “residuary beneficiary” to receive any unlisted belongings.

If you reside in a community property state—Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington, or Wisconsin—half of the assets accumulated during your marriage automatically belong to your spouse, irrespective of your will’s directives.

To avoid disputes, examine your state’s laws and relevant legal documents concerning asset distribution before drafting your will.

3. Consider Key Roles in Your Will

Identifying individuals for essential roles is a crucial part of writing your will. Always seek their consent, ensuring they fully understand their responsibilities.

- Beneficiaries: Outline how your assets should be distributed among your chosen beneficiaries. Consider a blend of percentage allocation and specific property assignment. For clarity, provide detailed descriptions of assets and instructions for asset distribution if a beneficiary predeceases you.

- Executor: Choose a trusted individual, ideally with legal or business experience, as executor. They manage debt settlement and property distribution. If potential disputes among beneficiaries exist, consider a neutral third party. Include a backup executor as a contingency plan.

- Guardian: Designate a guardian if you have or plan to have minor children. Factors like age, location, values, and financial stability should influence your choice. The same person could also be responsible for any pets.

- Witnesses: Most wills require at least two disinterested witnesses to sign in your presence. Refer to your state’s guidelines to ascertain the specific number required.

4. Consider Any Special Wishes

You can add special requests in your last will. For example, you can include a clause regarding the burial procedure or how your remains should be handled. There are many cases known when people leave unusual requests in their wills, like leaving all their estate to their pets. If you have something similar on your mind, make sure it complies with the local laws first.

5. Fill out and Finalize the Will Form

You can use the last will and testament template on this page or our comprehensive step-by-step builder for a foolproof process.

For a smoother probate process, consider making your last will and testament self-proving by attaching a self-proving affidavit.

6. Consider Post-creation Safeguards

Store your last will and testament in a secure yet easily accessible location, such as a safe or bank deposit box. Alternatively, entrust it to an attorney. Keep a record of its location, and ensure you or your spouse can find it if needed.

Informing your executor about the will’s whereabouts or providing them with a copy further bolsters its safety.

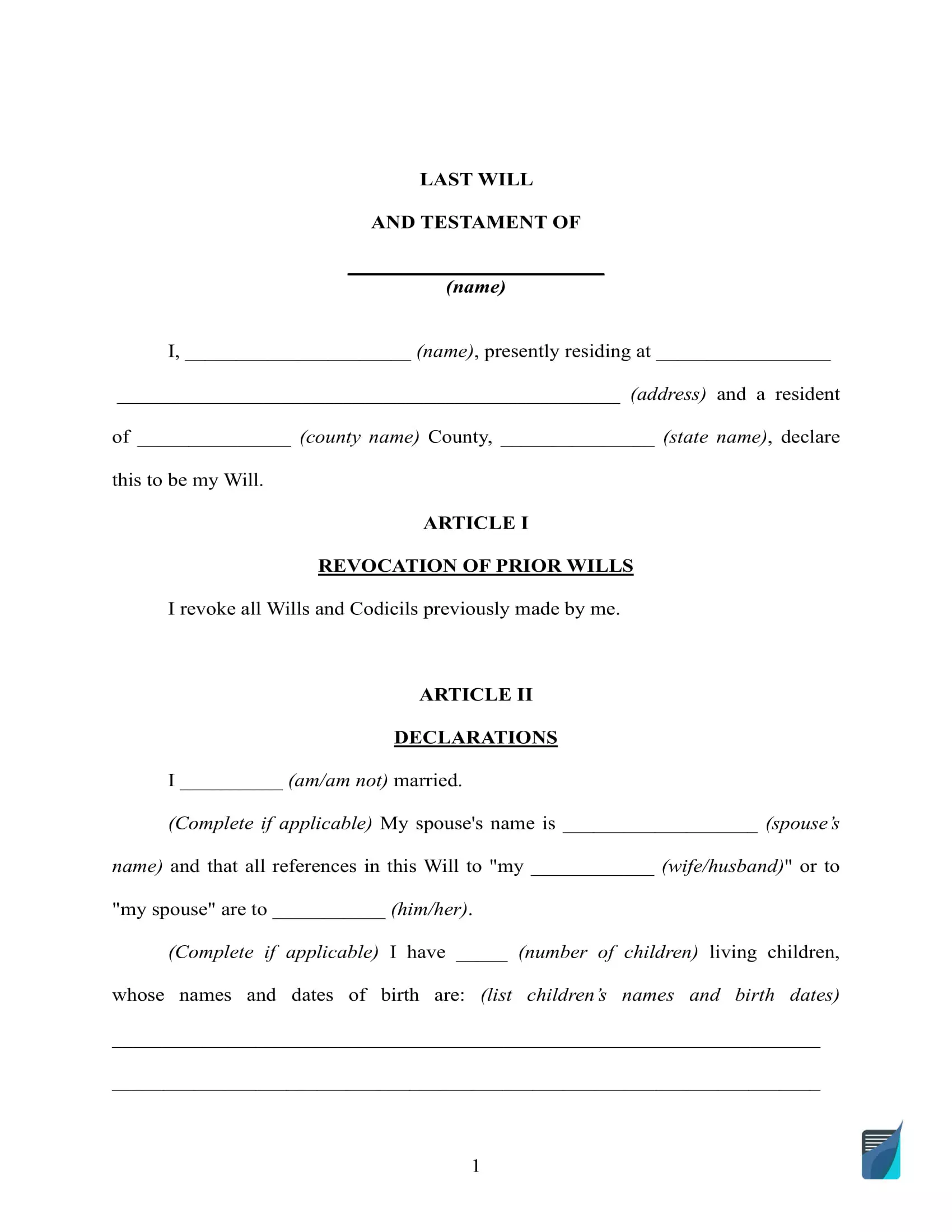

Download a Free Last Will Template

A basic last will and testament template usually suffices for most individuals’ legal needs. You can download a fillable template here, complete with specific instructions for all 50 U.S. states due to slight variations in state laws.

Our last will and testament builder guides you through the entire creation process, ensuring nothing important is overlooked. The result is a printable document filled with your provided information.

How to Fill Out a Last Will Template Step-by-Step

The first step of creating a last will and testament is to type one up. Courts are typically understanding if the language isn’t written in perfect legalese. But a few key points need to be covered first because a last will and testament is a legal document. That’s why using a last will and testament form is easier. Here’s a quick outline of what needs to be covered.

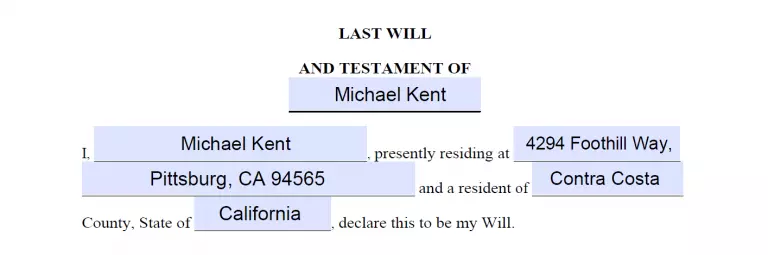

Step 1 – Establish the Testator

First, the top of the front page should have a header that says “Last Will and Testament of [Your Name].” This makes it clear that you were intentionally writing a will and not just expressing yourself.

The first paragraph should include your name, city, county, and state. This ensures that your will is going to be covered by the rules of your local jurisdiction.

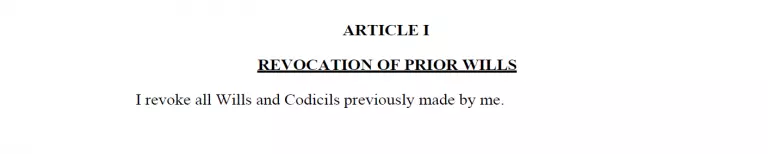

Step 2 – Include a Revocation Clause

The first clause should state that this is your “last” will, overriding any previous wills and codicils you may have written.

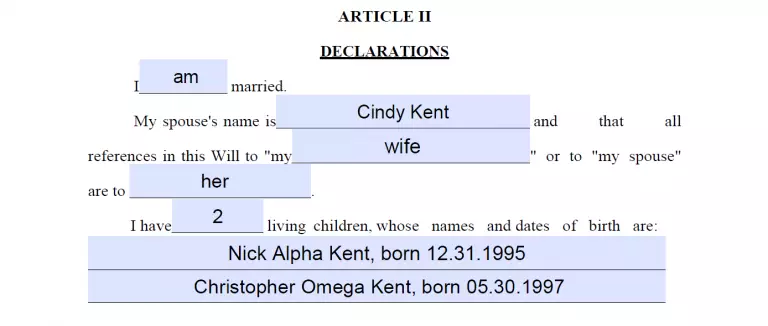

Step 3 – List Family Members

The second clause includes your family members—your spouse and child or children, if any. Their names should be mentioned along with the child/children’s birth dates. Also, there should be a sentence that you don’t have other living children and no issue of deceased children.

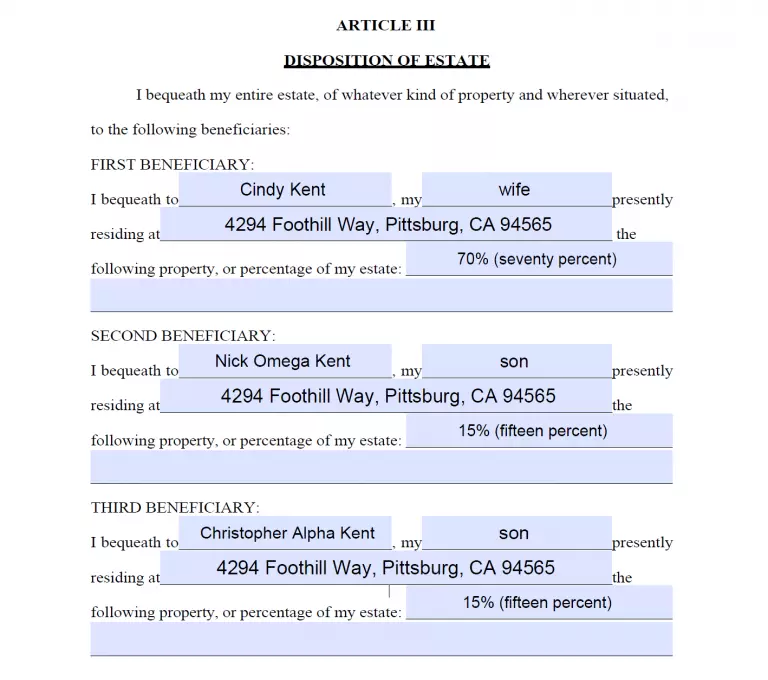

Step 4 – Indicate Beneficiaries and Their Shares

Next, name beneficiaries for your estate. For each beneficiary, include their name, address, and their relationship to you. Along with that, mention property or a percentage of your estate that you leave a certain beneficiary. Remember that you can either distribute your assets equally among all of your beneficiaries or leave a specific amount of assets to specific beneficiaries.

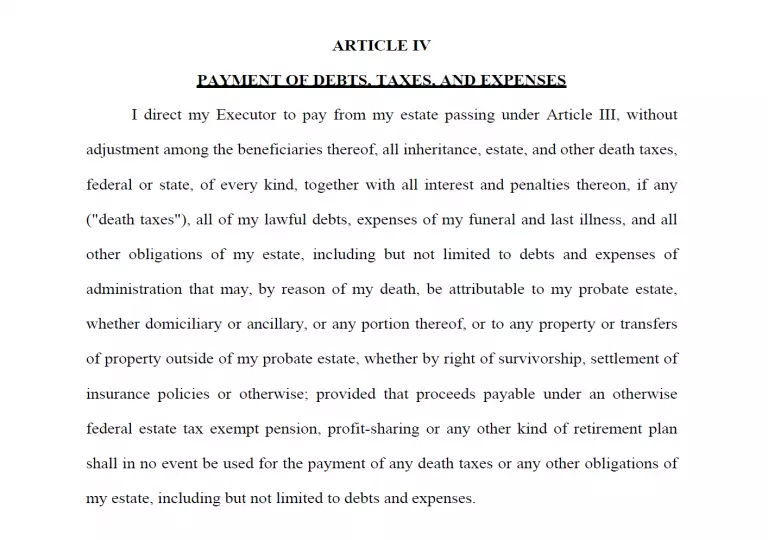

Step 5 – Cover Taxes and Other Expenses

When planning your estate, it’s crucial to understand the current tax laws. Your heirs may be liable for estate or inheritance taxes, which can significantly impact the value of the assets they receive.

The fourth clause covers debts, expenses, and taxes. It should authorize your executor to pay any funeral costs, estate tax, inheritance tax, and personal debts as soon as possible. It should also authorize them to settle any claims made against your estate.

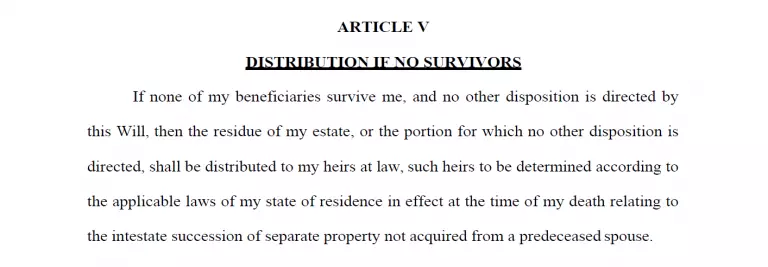

Step 6 – Fill Out the No Survivors Part

The next clause is called “Distribution if no survivors”. Here, briefly state what should be done to your property in case none of your beneficiaries survive you.

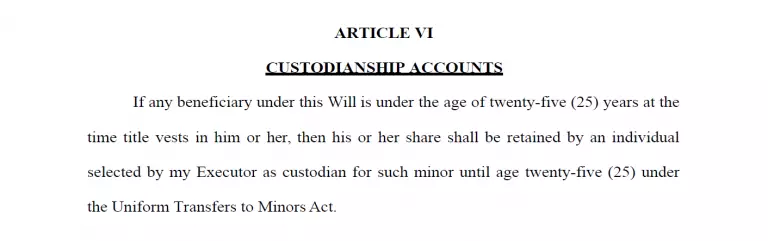

Step 7 – Review the Custodian Accounts Clause

The next clause, the “Custodianship Accounts”, is also short. It should simply say: “If any beneficiary under this Will is under the age of twenty-five (25) years at the time title vests in him or her, then his or her share shall be retained by an individual selected by my Executor as a custodian for such a minor until age twenty-five (25) under the Uniform Transfers to Minors Act.”

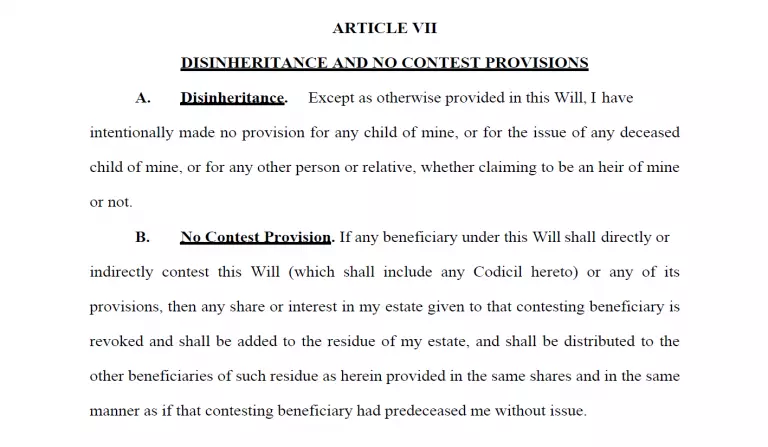

Step 8 – State If You Want to Disinherit Someone

The next clause is called the “Omission” or “Disinheritance” clause. Here, briefly state that any family members not named as beneficiaries are being intentionally omitted. In other words, you have left them out on purpose and not because you forgot.

It’s also a good idea to include a clause about contesting beneficiaries. It should state that if a beneficiary contests any part of or the entire document, their share is revoked and goes to other beneficiaries. This can deter people from suing your estate over their share of your assets.

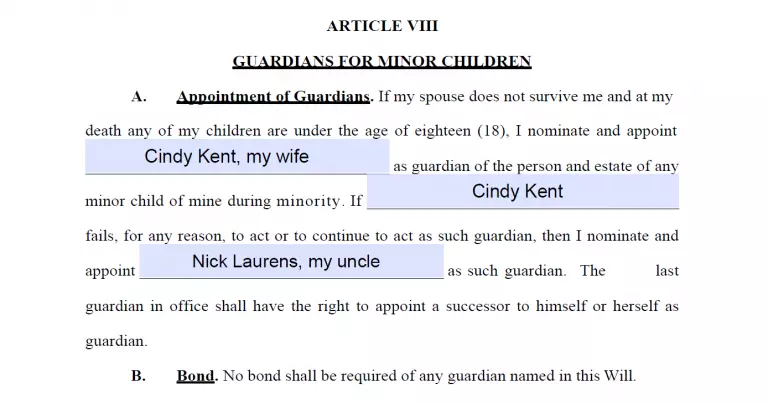

Step 9 – Assign a Guardian (optional)

If you have any dependents, you’ll want to assign a guardian. The guardian should have their name, city, county, and state listed in the will. Including an alternate guardian in case the first person fails to act as such is also a good idea. If you don’t have any dependents, you can skip this section.

In the same clause, you should mention: “No bond shall be required of any fiduciary serving hereunder, whether or not specifically named in this will, or if a bond is required by law, then no surety will be required on such bond.” Or, if you want to simplify the text, you can write: “No bond shall be required of any guardian named in this Will.”

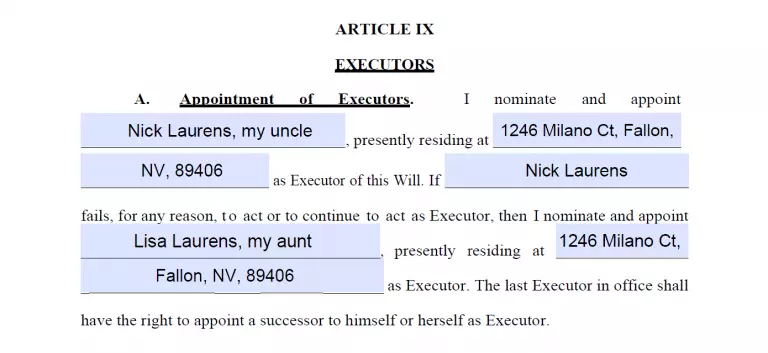

Step 10 – Establish Your Executor

The next clause assigns your executor. It should include their name, city, county, and state. In this section, it’s a good idea to appoint an alternate executor in case the first executor has passed away or is out of the country when you die.

Then, enumerate the powers of your executor. This clause is fairly long so we won’t get into too much detail, but it should authorize them to sell your property, rent it out if necessary, and manage your retirement plans, bank accounts, and stocks. It might also authorize them to hire a financial advisor or accountant for an estate plan.

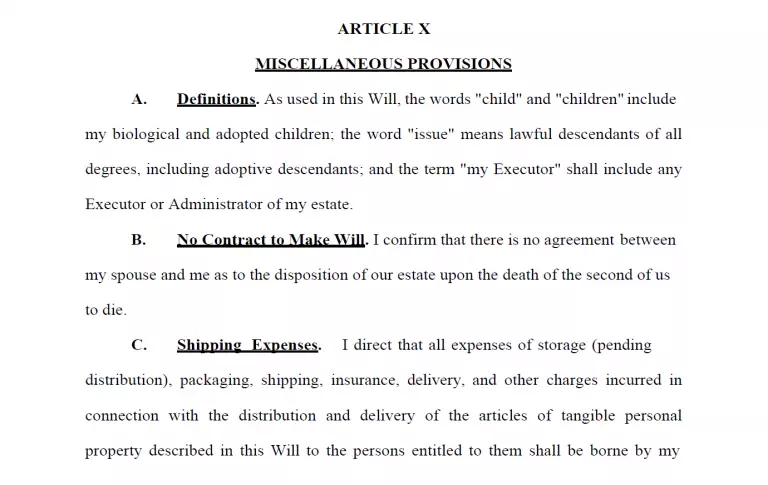

Step 11 – Review the Misc. Section

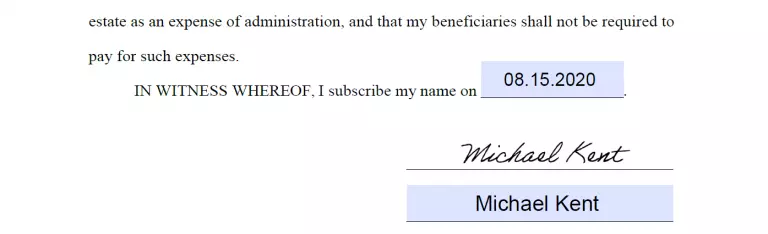

The last clause is called “Miscellaneous provisions”, and it includes the definitions of the terms that might be found ambiguous such as “child”, “issue”, and “my Executor”. In the next paragraph of the clause, include the words: “I confirm that there is no agreement between my spouse and me as to the disposition of our estate upon the death of the second of us to die.” After that, include a paragraph about shipping expenses saying that your beneficiaries shall not be required to pay the expenses connected with the delivery and distribution of the personal property mentioned in your will.

The clause should end with the words: “IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I subscribe my name…” and include the date you created it. Don’t forget to add your signature and printed name below the clause.

Step 12 – Sign the Will

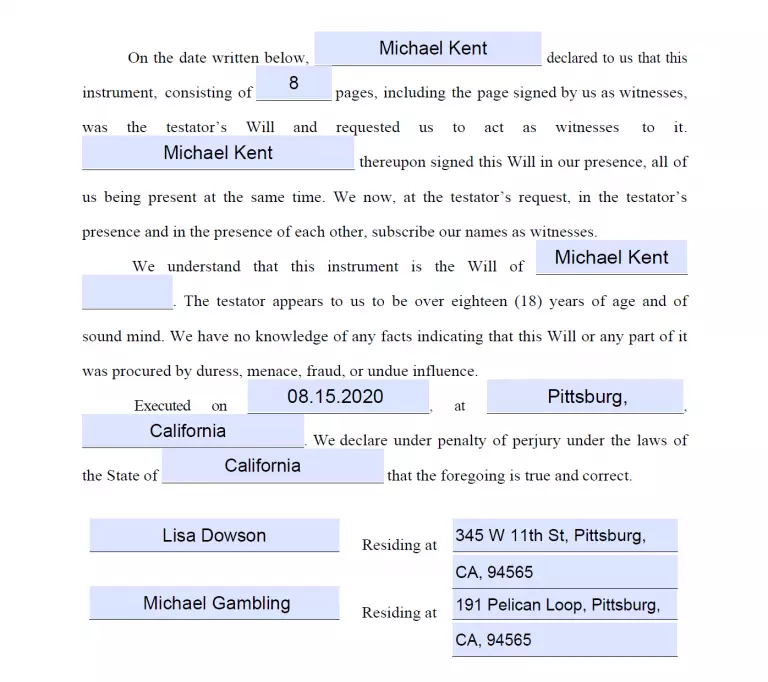

Now when your part of the writing is done, two attesting witnesses should be involved. They have to confirm that you created the will they are now signing and you requested them to act as witnesses. Then, they should mention that they witnessed the moment of you signing the will, and both were present simultaneously. After that, there should be a line: “We now, at the testator’s request, in the testator’s presence and in the presence of each other, subscribe our names as witnesses.”

In the second paragraph of the clause, the witnesses should affirm that you, as a testator, have met the state law requirements regarding age and soundness of mind and that the will was not procured by duress, menace, fraud, or undue influence.

The last paragraph of the clause should include the date and the place of execution of the will. The ending should be the following: “We declare under penalty of perjury under the laws of the (state) that the foregoing is true and correct,” with witnesses’ names, signatures, and places of residence written below the text.

Making It Valid

Next, you must find two witnesses you trust to verify your will’s authenticity. Similarly to the executor, the witnesses cannot be beneficiaries of the will. Write your signature, date the will in their presence, and have each sign it and print their address.

That’s all there is to it. Your will does not have to be notarized. However, if you have an affidavit, the affidavit will need to be notarized. We’ll get to that in a minute.

Last Will and Testament Signing Requirements by State

| STATES | Signing requirements | STATE LAW |

| Alabama | Two witnesses | Alabama Code, Sec. 43-8-134 |

| Alaska | Two witnesses | Alaska Statutes, Sec. 13.12.505 |

| Arizona | Two witnesses | Arizona Revised Statutes, Sec. 14-2505 |

| Arkansas | Two witnesses | Arkansas Annotated Code, Sec. 28-25-102 |

| California | Two witnesses | California Probate Code, Sec. 6112 |

| Colorado | Two witnesses OR a notary public | Colorado Revised Statutes, Sec. 15-11-502 |

| Connecticut | Two witnesses | Connecticut Revised Statutes, Sec. 45a-251 |

| Delaware | Two witnesses | Delaware Code, Title 12, Sec. 203 |

| Florida | Two witnesses | Florida Statutes, Sec. 732.504 |

| Georgia | Two witnesses | Georgia Code, Sec. 53-4-22 |

| Hawaii | Two witnesses | Hawaii Revised Statutes, Sec. 560:2-505 |

| Idaho | Two witnesses | Idaho Statutes, Sec. 15-2-505 |

| Illinois | Two witnesses | Illinois Compiled Statutes, Sec. 4-3 |

| Indiana | Two witnesses | Indiana Code, Title 29, Sec. 2 |

| Iowa | Two witnesses | Iowa Code, Sec. 633.280 |

| Kansas | Two witnesses | Kansas Statute, Sec. 59-606 |

| Kentucky | Two witnesses | Kentucky Revised Statutes, Sec. 394.040 |

| Louisiana | Two witnesses AND a notary public | Louisiana Civil Code, Book 3, Article 1581 |

| Maine | Two witnesses | Maine Probate Code, Title 18-C, Sec. 2-504 |

| Maryland | Two witnesses | Maryland Annotated Code, Sec. 4-102 |

| Massachusetts | Two witnesses | Massachusetts General Laws, Sec. 2-505 |

| Michigan | Two witnesses | Michigan Compiled Laws, Sec. 2505 |

| Minnesota | Two witnesses | Minnesota Statutes, Sec. 2-505 |

| Mississippi | Two witnesses | Mississippi Annotated Code, Sec. 91-5-1 |

| Missouri | Two witnesses | Missouri Revised Statutes, Sec. 474.330 |

| Montana | Two witnesses | Montana Annotated Code, Sec. 72-2-525 |

| Nebraska | Two witnesses | Nebraska Revised Statutes, Sec. 30-2330 |

| Nevada | Two witnesses | Nevada Revised Statutes,Sec. 133.040 |

| New Hampshire | Two witnesses | New Hampshire Revised Statutes, Sec. 551:2 |

| New Jersey | Two witnesses | New Jersey Statutes, Sec. 3B:3-7 |

| New Mexico | Two witnesses | New Mexico Annotated Statutes, Sec. 45-2-505 |

| New York | Two witnesses | New York Consolidated Laws, Sec. 3-2.1 |

| North Carolina | Two witnesses | North Carolina General Statutes, Sec. 31-8.1 |

| North Dakota | Two witnesses | North Dakota Century Code, Sec. 2-505 |

| Ohio | Two witnesses | Ohio Revised Code, Sec. 2107.06 |

| Oklahoma | Two witnesses | Oklahoma Statutes, Sec. 84-55 |

| Oregon | Two witnesses | Oregon Revised Statutes, Sec. 112.235 |

| Pennsylvania | Witnesses are required only in specific cases | Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes, Sec. 2502 |

| Rhode Island | Two witnesses | Rhode Island General Laws, Sec. 33-5-5 |

| South Carolina | Two witnesses | South Carolina Code of Laws, Sec. 62-2-502 |

| South Dakota | Two witnesses | South Dakota Codified Laws, Sec. 29A-2-505 |

| Tennessee | Two witnesses | Tennessee Annotated Code, Sec. 32-1-103 |

| Texas | Two witnesses | Texas Statutes, Estates Code, Sec. 251.051 |

| Utah | Two witnesses | Utah Code, Sec. 75-2-505 |

| Vermont | Two witnesses | Vermont Statutes, Title 14, Sec. 5 |

| Virginia | Two witnesses | Virginia Code, Sec. 64.2-403 |

| Washington | Two witnesses | Washington Revised Code, Sec. 11.12.020 |

| West Virginia | Two witnesses | West Virginia Code, Sec. 41-1-3 |

| Wisconsin | Two witnesses | Wisconsin Statutes and Annotations, Sec. 853.03 |

| Wyoming | Two witnesses | Wyoming Statutes, Sec. 2-6-112 |

How to Change Your Will

Changing your will is the same as creating a new one, including two witness signatures. However, once you’ve changed the will, you’ll want to ensure that the previous will is destroyed along with any copies. You can also create a codicil for minor changes, which we’ll talk about shortly.

So, why would you want to change your will? Several life events are significant enough to merit creating a new will. These include:

- Getting married

- Getting a divorce

- If you’re in a same-sex marriage that was officiated before the 2015 Supreme Court decision

- Common-law marriage

- A new domestic partnership

- The birth of a new baby or an adoption

- A new stepchild

- Death of a child, spouse, or other beneficiaries

- Adding or removing a beneficiary

- Moving from a common law property state to a community property state, or the other way around

- A significant change in your estate’s value

- Changing guardians for your dependents

Related Documents

In addition to disbursing your personal property, there are a few other matters that you might want to attend to in your will. Moreover, you might want to make minor changes to your will. Here are a few documents that you should continue storing with your last will and testament.

Codicil to Will

A codicil is a document that specifies minor changes to your will. Instead of writing an entirely new will, you can write a shorter, simpler document to change your final wishes.

So, what counts as a minor change? There are no cut-and-dry legal rules. Codicils are typically used to change the executor, update the names and addresses of beneficiaries, or add a new request for a newly-obtained asset, such as a new home. Anything beyond that, and you should write a new will. You can write multiple codicils. However, if you’ve written more than three or four, consider writing a new will to make things easier on your executor. A codicil has the same requirements as your original will, so make sure to get your two witnesses.

Self-proving Affidavit

A self-proving affidavit is designed to make it easier for your executor to get your will through probate. With an affidavit, your will is automatically considered legally valid, and managing your estate will be quick and painless. Without one, proving your will’s authenticity can be burdensome. You’ll also need a stamp from a notary public. Without one, your affidavit won’t be valid. In fact, under Louisiana state law, an unnotarized affidavit will invalidate your entire will.

Living Trust

A living trust allows you to avoid probate by putting your assets in the possession of a trust. A trust is a separate legal entity and is governed by a manager, typically you. Upon your death, the trust’s assets will be disbursed to your heirs without the need for probate. That said, it’s still a good idea to have a simple will covering tangible personal property not owned by the trust.

Living Will

A living will, also called a health care directive, states your wishes regarding end-of-life medical treatment and life-prolonging medical procedures.

By now, you probably feel like you’re ready to write your will, but we should cover a few more things before we wrap up. So, let’s take some time to answer a few frequently asked questions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do I have to create a will?

A person who dies without a will dies “intestate” in legalese. In this case, the law has provisions to distribute your assets. Creating a will allows you to determine what individuals will receive ownership of your funds and under what conditions. Depending on your personal circumstances, this could mean a spouse, parents, children, siblings, or even aunts, uncles, nieces, and nephews.

If you have no living relatives, your entire estate will go to the government. So even if you’re truly alone in this world, you might want to create a will to leave your assets to charity.

What can happen if I don't leave a will?

If you die without a will, local state laws dictate asset distribution. Typically, assets go to your closest kin: for singles, that’s parents and then siblings; for singles with children, it’s their offspring. The spouse inherits everything for married individuals, though children from previous relationships receive half.

Complications arise with domestic partnerships. Depending on state laws, partners may inherit as a spouse or nothing at all. For unrecognized relationships, the partner inherits nothing without a valid will. Hence, a will is crucial to protect your loved ones and your intentions.

What documents should go along my will?

In addition to your will, comprehensive estate planning necessitates several other documents:

- Power of Attorney: These forms, one for finances and another for healthcare, designate a trusted individual to make decisions on your behalf in case of incapacitation.

- Statement of Desire: Though not legally binding, it communicates your preferences for funeral arrangements and the handling of your remains, assuming your executor will respect your wishes.

- Information Sheet: This contains crucial data like online account details, financial numbers, debt repayment plans, location of assets, and contacts to be informed of your demise.

Together, these documents ensure effective management of your affairs in line with your desires.

Is it possible to create a will on your own?

In the US, any mentally competent adult can write a will. As we’ve already mentioned, a few technical requirements need to be met, but beyond that, there are no further requirements. You don’t have to register with any government agency or court. However, some states allow you to do this to make the probate process easier. For most purposes, it’s enough to keep your will in a safe place and to make sure that your executor knows its location.

What do I have to consider before writing a will?

Before crafting a will, assess your assets and intended beneficiaries. Also, consider your debts; while not inherited by heirs, they must be settled by your estate before distribution.

If you have minors, identify their potential guardian who understands the gravity of this role. Discussing these duties beforehand is essential.

The same applies to the executor of your will due to their significant responsibility.

Lastly, cater to unique needs, like guardianship for dependent elderly relatives or disabled adult children. Considering these points ensures a comprehensive will that meets your specific circumstances.

What happens if I die in a different state or abroad?

Regardless of where you die, your last will and testament stays legally binding. If you die out of state, the local police will notify your next of kin. If you die overseas, the local police will notify the American embassy, which in turn will notify your next of kin. That said, your next of kin will be responsible for any transportation expenses involved with returning the body.

Can I find a person's will online?

It depends. A will is considered a private document if the person is still alive. The only way to see it is to ask the person who wrote the will, and no one can force them to show it. If the person is already dead, the will remains private until it has been filed at the probate court. At that time, it becomes a public record. Most probate courts now post their records online.

| Related documents | Do you need to create it along with the last will? |

| Codicil | Yes, if you want to make one or several minor changes to your will. |

| Self-proving affidavit | Yes, if you want to facilitate the probate. |

| Living will | Yes, if you also want to state your wishes regarding end-of-life medical treatment and life-prolonging medical procedures. |

| Living trust | Yes, if you want to avoid probate by putting your assets in the possession of a trust. |